Yimiyanke x Haaliyanke x Murtudo! (1)

“You’ll see: my words jolt and clang like chains. Words that detonate, bust, unscrew, overthrow, torture! Words that whack, slap, break, and grind! If anyone feels uncomfortable, they can be on their way.”

Calixthe Beyala, Femme nue, femme noire

A thick cream-coloured sheet of paper sits there, on the windowsill. Other pages, upright, stand guard, covered in black faces. One step back and I can make out their features better: engraved figures printed using wooden stamps. Behind these pieces of paper, the green leaves of a garden emerge. It is a Parisian garden; cold, but sunny. Hamedine Kane’s residency at the Cité des Arts is coming to an end. And I am discovering his woodcuts for the first time.

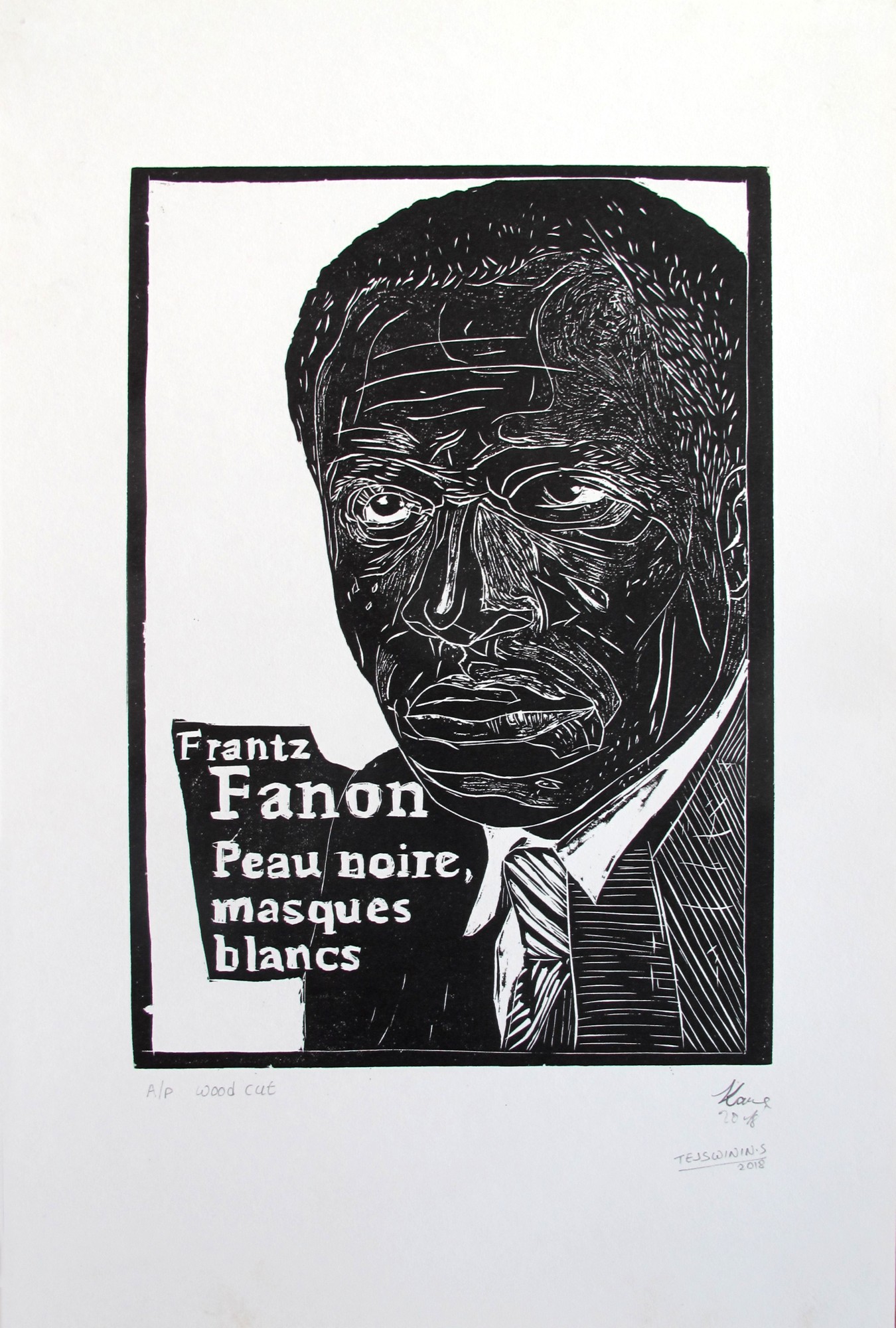

I couldn’t simply explain what happened during this first encounter, but something like a poem written in tandem was drawn onto the walls of a house. Hamedine was working on his project Trois Américains à Paris, which takes the paths of a trio of Afro-American writers exiled in France as its starting point: Richard Wright, Chester Himes, and James Baldwin. In the space of his studio, he created a shelter for their words, a hut made of struts and fabric, on which we started a poem. Capturing the books that littered the floor of the studio, we chose passages from Calixthe Beyala, Frantz Fanon, and others, that we inscribed on its framework. Without any big speeches, without speaking much either, except to share other people’s words, we simply created the space for an encounter.

This Trois Américains project follows a corpus, Salesman of Revolt(2), initiated in 2018 in Mumbai with Indian artist Tejswini Narayan Sonawane, and exhibited at the Dakar Biennale in 2018, or more recently at the Palais de la Porte Dorée (3). Kane approaches the impact of racial struggles on African and Western societies indirectly, via a series of etchings, representing book covers sold by young retailers in African public squares. Sometimes illiterate, the latter nevertheless boast the merits of poetic or revolutionary books, from Cheikh Anta Diop to Ta-Nehisi Coates, which they sell on the side of the road. On their heads, they are sporting decades of Black literary and revolutionary heritage, traces of a combat against colonialism that is far from over.

This poetic way of inhabiting the world, I was to find again, later, in the films of Hamedine Kane. Each of his videos constitutes a kind of hut to harbour words and worldviews. In the one whose title I’ve borrowed (4), we walk in the artist’s footsteps, in the sand, as he drifts, roams, or rambles. Synecdochally, we read in them the thousands of footsteps by thousands of migrants who leave the coasts for Europe or other possible shores. To be in the world, we must be in motion(5) the artist said on a radio show. Similarly, the artwork bears within it the myths of “flâneurs” such as those imagined by Charles Baudelaire in Le Peintre de la Vie moderne(6) or those of contemporary walkers, including British national Hamish Fulton and the Afro-Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth(7). Walk, walk, walk repeats the artist. Along with words, he provides images: scenes from customs, feet fleeing, migrants at train stations, feet fleeing, road maps, feet…

Several years later, he met Ayesha Hameed, an artist and academic whose work builds on Paul Gilroy’s research on the concept of the Black Atlantic(8). Together, they made A l’ombre de nos fantômes [In the Shadows of Our Ghosts], which tells the story of eleven migrants found dead aboard a ship that had drifted for four months from Cap-Vert to the coast of Barbados, filled with migrants. The film works in layers: sequences present the walker filming his shadow, suddenly covered by other images of an enraged ocean. The violence of the political status quo is not shown frontally, but the avatars of Mami Wata, the ocean goddess who swallows up bodies, are heard one by one on the soundtrack, with the effect of a wave. Metaphors of devastating migratory policies, these waves make “A l’ombre” a personal work: we navigate on the very surface of the skin, stuck to the filming body, the eyelash over the eye of the camera. Hamedine Kane chants Edouard Glissant’s text “Il n’est frontière qu’on outrepasse”, reworked to express his conception of exile: “Carthage and black salt / And the belly of the slave ships / Gabelle taxes and salt / Red / And Hiroshima / And Nagasaki / Abd-El-Kader’s Smala … And the Timbuktu Library / New Orleans / And its water Katrina / Since forever …” Glissant went even further: “We are drawn to borders, not because they are signs or elements of the impossible but because they are places of passage and transformation… . That is why we need borders, not as places to stop at, but as the point at which we may exercise that right of free passage from the same to the Other; savour the wonder of here and there… . Borders exist for the fulfilment that we derive from crossing them, and by so doing sharing the full impact of difference”(9). It is possibly what Kane puts into play with each collaboration, with Hameed, Sonawane, Glissant, the Belgian filmmaker Benoît Mariage who took him under his wing to learn filmmaking, or with me, that day in the hut.

Yimiyanke Haaliyanke…

Murtuɗo!

“The paradox - and a fearful paradox it is - is that the American Negro can have no future anywhere, on any continent, as long as he is unwilling to accept his past. To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it”(10).

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

“People like they historical shit in a certain way. They like it to unfold the way they folded it up. Neatly like a book. Not raggedy and bloody and screaming”(11).

Suzan-Lori Parks, Topdog/Underdog

Hamedine Kane evokes the importance of the Pulaar poems (12) of Mammadu Sammba Joob, nicknamed Murtuɗo, ‘the revolt’. They seem to have the tone of firepower that my exchanges with Kane often have. As soon as you reflect on his work, working back up the strands of his genealogical tree, you encounter activism: his uncle, the professor Saïdou Kane, a socio-anthropologist and founder of the Union Démocratique Mauritanienne (UDM) was in favour of his writing, including the Manifeste du Négro-mauritanien Opprimé [Manifesto of the Oppressed Black Mauritanian] (1986). Further up on one branch, you’ll come across Elimane Boubacar Kane, an anticolonial resistant and founding figure of Futa Tooro, the border region between Mauritania and Senegal, where Kane was born.(13) This first name, Elimane, functions as a code name throughout his work. Kane is partly the product of migratory movements of African intellectuals, which, after studying in Russia, became the first executives of newly independent African states, marking the official end of French colonisation.

His interest in politics subsequently emerges in all of his acts, from walking to speaking, via the camera. As Baldwin urged, Hamedine Kane questions the way in which politics forms narratives. This is the case in Déclaration de Politique générale(14): he draws parallels between the 1776 ‘toroodo’ revolution in Futat and that of contemporary Senegal Similarly, since 2018, he has worked in a collective, as part of the École des Mutants cofounded with his friend Stéphane Verlet-Bottero. This research group, whose members have changed over the years, focuses on the role academic utopia have played in post-independency processes and the construction of African nation states. Several artists and researchers have found themselves under this umbrella, including Boris Raux, Lou Mo, or Valérie Osouf, to study together the heritage of transnational movements: the Non-Aligned, Afro-Asianism. Deliberately antihierarchical and nomadic, the School takes different forms depending on the project: publications, collective video works, or sculptural installations. His name connects him to the University of Mutants, founded in 1977 on Gorée (Senegal) and to the abortive one of Futur Africain, co-financed by many African states and Taiwan in the 1990s, with the aim of promoting decolonial epistemological knowledge. Where the school is the most fertile is when it gives rise to assemblies that enable collective examination of how to deconstruct and reconstruct the inherited pedagogical ideologies and structures by recentering African discourse and writing at the heart of global political and social history. When it is based on the imaginary of the ‘mutant’ as devised by writer Octavia Butler or by Glissant, as was the case in Sébi-Ponty, during the Assembly that Kane coorganised in 2019. There, the School presents the power of civil society in action, or, to cite a text beloved of the artist, reminds us that “nothing important is ever done without a non-historic horde“,everyone discussed the vertiginous power of revolutionary futures(15)

The most revolutionary thing about Hamedine Kane’s work is his way of life. The film La Maison Bleue, which he signed in 2020, shows this clearly. In it, the director follows in the footsteps of a friend, Alpha, who lives in the Calais Jungle, in a shack that he built himself in the middle of the migrant camp. When he hears his voice on the radio, Hamedine Kane decides to join Alpha Diagne, his childhood friend, and for several months, he will live in this Fulani hut in the middle of the Calais jungle, sharing both Alpha’s story and history, from West Africa to Istanbul, Greece, and the Balkans. It is this proximity with the subject, these shared space-times, that make the filmic work of Hamedine Kane a kind of Deleuzian war machine. In Mille Plateaux, he reminded us that the latter are not defined by their warlike property, but instead “by a certain way of occupying, of filling up space-time, or inventing new space-times: revolutionary movements, but also art movements represent these kinds of war machines”(16.) Kane is extremely generous: with me, he exchanged knowledge and science, often books; but most importantly, he shared his time.

1 Ce titre pourrait se traduire par Hamedine Kane. Poète x Orateur x Révolté! mais pourquoi le traduire ?

2 En français, on dirait cessionnaire de révolte.

3 Ce qui s’oublie et ce qui reste, par Meriem Berrada, Musée national de l’histoire de l’Immigration, Paris, mai–août 2021.

4 Hamedine Kane, Habiter le Monde 2016, 14 min.

5 Un habitant du monde nommé Hamedine Kane dans En Sol Majeur, RFI, 26 juin 2022, accessible via

https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/en-sol-majeur/20220626-un-habitant-du-monde-nomm%C3%A9-hamedine-kane.

6 Charles Baudelaire, Peintre de la Vie moderne, 1860, published in Le Figaro from 1863 onwards.

7 Paulo Nazareth walked for six month as part of a performative project Noticias de America, which consisted of reaching the United States on foot from Belo Horizonte in southern Brazil.

8 Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, 1993. It is a reference work on Black issues that traces affinities between African, American, British, and Caribbean experiences. Hameed is a professor at Goldsmiths in London, where Gilroy taught for a long time.

9 Edouard Glissant, Il n’est frontière qu’on n’outrepasse in Le Monde diplomatique, October 2006, page 16, accessible via http://www.lutecium.fr/www.ecole-lacanienne.net/documents/actualite/ilnestfrontiere.pdf. See also the English version here: https://mondediplo.com/2006/11/13frontiers)

10 James Baldwin, “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind” in The Fire Next Time, 1963, 81. (See also https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind)

11 Suzan-Lori Parks, Topdog/Underdog (New York: Dramatists Play Service Inc., 1999), 57.

12 The artist’s native language.

13 Mamoudou Sy, La vallée du fleuve Sénégal dans le jeu des échelles politiques : le Dimar aux 18e et 19e siècles, 2018, 276 p.

14 Hamedine Kane, Déclaration de Politique générale, 2018, 15 min.

15 Gilles Deleuze, Le devenir révolutionnaire et les créations politiques in Multitudes, 1990, n.p.

16 Deleuze, Le devenir révolutionnaire, 1990, n.p.

Yimiyanke x Haaliyanke x Murtudo! (1)

“Vous verrez : mes mots à moi tressautent et cliquettent comme des chaînes. Des mots qui détonnent, déglinguent, dévissent, culbutent, torturent ! Des mots qui fessent, giflent, cassent et broient ! Que celui qui se sent mal à l’aise passe sa route.”

Calixthe Beyala, Femme nue, femme noire

Une feuille de papier épais, crème, se tient là, sur le rebord d’une fenêtre. D’autres pages, debout, montent la garde, recouvertes de visages noirs. Un pas de recul et je distingue mieux leurs traits, gravures de figures imprimées au tampon de bois. Derrière ces feuilles de papier, celles, vertes, d’un jardin se dessinent. Un jardin parisien. Il fait froid, mais beau. Hamedine Kane termine sa résidence à la Cité des Arts. Et je découvre ses gravures pour la première fois.

Il sera peut-être malaisé d’expliquer ce qui se passe pendant cette première rencontre mais quelque chose comme un poème rédigé à quatre mains se dessine sur les murs d’une maison. Hamedine travaille à son projet Trois Américains à Paris qui prend comme point de départ les chemins d’un trio d’écrivains afro-américains exilés en France : Richard Wright, Chester Himes et James Baldwin. Dans l’espace de son atelier, il crée un abri pour leurs mots, une cabane de poutrelles et de tissu, sur laquelle nous débutons l’écriture d’un poème. Saisissant les livres qui jonchent le sol de l’atelier, nous choisissons des passages de Calixthe Beyala, Frantz Fanon, et d’autres, que nous venons inscrire sur sa charpente. Sans grand discours, sans beaucoup se parler non plus, sauf pour échanger les mots d’autres, nous créons simplement l’espace d’une rencontre.

Ce projet des Trois Américains fait suite à un corpus, Salesman of Revolt(2), initié en 2018 à Mumbai avec l’artiste indienne Tejswini Narayan Sonawane, et exposé à la biennale de Dakar en 2018, ou plus récemment au palais de la Porte Dorée.(3) Kane y aborde de biais l’impact des luttes raciales dans les sociétés africaines et occidentales via un ensemble de gravures, représentant les couvertures de livres vendus par de jeunes commerçants sur les places publiques africaines. Ne sachant parfois pas lire, ces derniers vantent néanmoins les mérites d’ouvrages poétiques ou révolutionnaires, de Cheikh Anta Diop à Ta-Nehisi Coates, dont ils font le commerce sur le bord de la route. Sur leurs têtes, ils arborent ainsi des décennies d’héritage littéraire et révolutionnaire noir, traces d’un combat contre le colonialisme qui est loin d’être éteint.

Cette manière poétique d’habiter le monde, je l’ai retrouvée, plus tard, dans les films d’Hamedine Kane. Chacune de ses vidéos constitue une sorte de cabane pour abriter mots et regards sur le monde. Dans celle dont j’ai emprunté le titre (4), on suit les pas de l’artiste, dans le sable, alors qu’il vogue, erre, ou divague. De manière synecdotique, on y lit les milliers de pas de milliers de migrants qui quittent les côtes pour rejoindre l’Europe, ou d’autres rivages possibles. “Pour être dans le monde, il faut être en mouvement”(5) disait l’artiste dans une émission radiophonique. De même, l’oeuvre charrie avec elle les mythes de flâneurs tels qu’imaginés par Charles Baudelaire dans Le Peintre de la Vie moderne (6), ou celles de marcheurs contemporains, dont le britannique Hamish Fulton et l’artiste afro-brésilien Paulo Nazareth.(7) “Marche, marche, marche” ressasse l’artiste. Aux mots, il appose des images : scènes de douane, pieds qui fuient, migrants en gare, pieds qui fuient, cartes routières, pieds qui…

Quelques années plus tard, il rencontre Ayesha Hameed, une artiste et universitaire dont le travail prolonge les recherches de Paul Gilroy autour du concept de “Black Atlantic”(8). Ensemble, ils réalisent A l’ombre de nos fantômes, qui relate l’histoire de onze migrants retrouvés morts à bord d’un navire ayant dérivé quatre mois depuis le Cap Vert jusqu’aux côtes de la Barbade, empli de migrants. Le film opère par couches : des séquences donnent à voir le marcheur filmant son ombre, soudain recouvertes par d’autres images d’océan enragé. La violence du fait politique n’est pas montrée de front, mais les avatars de Mami Wata, la déesse océan qui avale les corps, s’égrènent sur la bande-son, avec l’effet d’une vague. Métaphores de politiques migratoires dévastatrices, ces déferlements font d’A l’ombre une oeuvre intime : on y navigue à la surface même de la peau, collé.es au corps filmant, le cil sur la lentille de la caméra. Hamedine Kane y scande le texte d’Edouard Glissant “Il n’est frontière qu’on outrepasse”, retravaillé pour traduire sa conception de l’exil : “Carthage et le sel noir/Et le ventre de ces bateaux négriers/Les gabelles et le sel/Rouge/Et Hiroshima/Et Nagasaki/La smala d’Abdelkader (…) Et la bibliothèque de Tombouctou/La Nouvelle Orléans/Et ses Katrina d’eau/Depuis toujours…” Glissant allait plus loin encore : “nous fréquentons les frontières, non pas comme signes et facteurs de l’impossible, mais comme lieux du passage et de la transformation. (…) C’est pourquoi nous avons besoin des frontières, non plus pour nous arrêter, mais pour exercer ce libre passage du même à l’autre, pour souligner la merveille de l’ici-là. Il n’y a de frontière que pour cette plénitude enfin de l’outrepasser, et à travers elle de partager à plein souffle les différences”(9). C’est peut-être ce que Kane met en jeu à chaque collaboration, avec Hameed, Sonawane, Glissant, le cinéaste belge Benoît Mariage qui le prit sous son aile pour lui apprendre le cinéma, ou encore avec moi, ce jour dans la cabane.

Yimiyanke Haaliyanke… Murtuɗo!

“Le paradoxe - et il est effrayant - est que le Noir américain n’a et n’aura d’avenir nulle part, sur aucun continent tant qu’il ne se résoudra pas à accepter son passé. Accepter son passé, son histoire, ne signifie pas s’y noyer ; cela signifie apprendre à en faire bon usage.”(10)

James Baldwin, La Prochaine Fois, le Feu

“People like they historical shit in a certain way. They like it to unfold the way they folded it up. Neatly like a book. Not raggedy and bloody and screaming.”(11)

Suzan-Lori Parks, Topdog/Underdog

Hamedine Kane évoque l’importance des poèmes pulaar(12) de Mammadu Sammba Joob, surnommé Murtuɗo, “le révolté”. Ils me semblent avoir la tonalité de la poudre que mes échanges avec Kane ont souvent. Dès qu’on s’interroge sur son travail, remontant les lianes de son arbre généalogique, on rencontre le militantisme : son oncle, le professeur Saïdou Kane, socio-anthropologue et fondateur de l’Union Démocratique Mauritanienne (UDM) fut pour ses écrits, dont le Manifeste du Négro-mauritanien Opprimé (1986). Plus loin sur une branche, on croise avec Elimane Boubacar Kane, résistant anticolonial et figure fondatrice du Futa Tooro, la région frontalière de la Mauritanie et du Sénégal où Kane est né (13). Ce prénom, Elimane, opère d’ailleurs comme un nom de code au travers de son oeuvre. Kane est en partie le produit de mouvements migratoires d’intellectuels africains, qui, après avoir étudié en Russie, devinrent les premiers cadres d’états africains nouvellement indépendants, marquant la fin officielle de la colonisation française.

L’intérêt pour la question politique se manifeste dès lors dans chacun de ses gestes, de la marche à la parole, en passant par la caméra. Comme Baldwin exhortait à le faire, Hamedine Kane s’interroge sur la manière dont le fait politique fait récit. C’est le cas dans Déclaration de Politique générale(14) : il y met en parallèle la révolution “toroodo” de 1776 au Futa, et celle du Sénégal contemporain. De même, depuis 2018, il travaille en collectif, au sein de l’École des Mutants co-fondée avec son ami Stéphane Verlet-Bottero. Ce groupe de recherche, dont les membres fluctuent, s’intéresse au rôle qu’ont joué les utopies académiques dans les processus de postindépendances et de construction d’état-nations africains. Plusieurs artistes et chercheur.euses se retrouvent sous cette ombrelle, dont Boris Raux, Lou Mo, ou Valérie Osouf, pour étudier ensemble l’héritage de mouvements transnationaux -les Non-Alignés, l’Afro-Asianisme. Volontairement antihiérarchique et nomade, l’École prend des formes différentes selon les projets : publications, oeuvres vidéo collectives ou installation sculpturale. Son nom la rattache à l’université des mutants fondée en 1977 à Gorée (Sénégal) et à celle, avortée, du Futur Africain, co-financée par de nombreux États africains et Taiwan dans les années 1990, dans l’optique de promouvoir les savoirs épistémologiques décoloniaux. Là où l’école est la plus fertile, c’est lorsque qu’elle donne lieu à des assemblées qui permettent de penser à plusieurs comment déconstruire et reconstruire les idéologies et structures pédagogiques héritées en recentrant les discours et écrits africains au coeur de l’histoire politique et sociale globale. Lorsqu’elle s’appuie sur l’imaginaire du ‘mutant’ tel que pensé par l’écrivaine Octavia Butler ou par Glissant, comme ce fut le cas à Sébi-Ponty, lors de l’Assemblée que Kane coorganise en 2019. Là, l’École donne à voir la puissance de la société civile en acte, ou, pour citer un texte cher à l’artiste, nous rappelle que “rien d’important ne se fait sans une “nuée non-historique””, tous.tes conversant ensemble de la puissance vertueuse des “devenirs révolutionnaires”(15).

Ce qu’il y a de plus révolutionnaire dans le travail d’Hamedine Kane, c’est sa façon de vivre. Le film La Maison Bleue, qu’il signe en 2020, le montre de manière claire. Dans ce dernier, le réalisateur suit les pas d’un ami, Alpha, qui vit dans la “Jungle de Calais”, dans une cahute qu’il s’est construite au milieu du campement migrant. Lorsqu’il entend sa voix à la radio, Hamedine Kane décide de rejoindre Alpha Diagne, son ami d’enfance, et pendant plusieurs mois, il vivra dans cette case peule au milieu de la jungle de Calais, partageant avec Alpha son histoire, depuis l’Afrique de l’Ouest vers Istanbul, la Grèce, et les Balkans. C’est cette proximité avec le sujet, ces espaces-temps partagés qui font du travail cinématographique d’Hamedine Kane une sorte de “machine de guerre” à la Deleuze. Dans Mille Plateaux, il rappelait que ces derniers ne se définissent pas par leur vertu guerrière, mais plutôt “par une certaine manière d’occuper, de remplir l’espace-temps, ou d’inventer de nouveaux espaces-temps : les mouvements révolutionnaires, mais aussi les mouvements d’art sont de telles machines de guerre”(16). Avec Hamedine Kane, on s’arme de sciences et de savoir, de livres, souvent, mais surtout, on prend le temps.

__

1 Ce titre pourrait se traduire par Hamedine Kane. Poète x Orateur x Révolté! mais pourquoi le traduire ?

2 En français, on dirait ‘cessionnaire de révolte’.

3 Ce qui s’oublie et ce qui reste, par Meriem Berrada, Musée national de l’histoire de l’Immigration, Paris, mai–août 2021.

4 Hamedine Kane, Habiter le Monde, 2016, 14 min.

5 “Un habitant du monde nommé Hamedine Kane” dans En Sol Majeur, RFI, 26 juin 2022, accessible via https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/en-sol-majeur/20220626-un-habitant-du-monde-nomm%C3%A9-hamedine-kane.

6 Charles Baudelaire, “Peintre de la Vie moderne”, 1860, publié dans Le Figaro à partir de 1863.

7 Paulo Nazareth a marché pendant six mois dans le cadre d’un projet performatif, “Notícias de América” qui consistait à rejoindre les Etats-Unis à pied depuis Belo Horizonte, au sud-est du Brésil.

8 Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, 1993. Il s’agit d’un ouvrage de référence sur la question noire qui trace les affinités entre expériences noires africaines, américaines, britanniques et caribéennes. Hameed est professeure au Goldsmiths à Londres, où Gilroy a longtemps enseigné.

9 Edouard Glissant, “Il n’est frontière qu’on n’outrepasse” in Le Monde diplomatique, octobre 2006, page 16, accessible via http://www.lutecium.fr/www.ecole-lacanienne.net/documents/actualite/ilnestfrontiere.pdf.

10 James Baldwin, “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind” in The Fire Next Time, 1963, p. 81.

11 Suzan-Lori Parks, Topdog/Underdog”, Dramatists Play Service Inc., 1999, p. 57

12 La langue native de l’artiste.

13 Mamoudou Sy, La vallée du fleuve Sénégal dans le jeu des échelles politiques : le Dimar aux 18e et 19e siècles, 2018, 276 p.

14 Hamedine Kane, Déclaration de Politique générale, 2018, 15 min.

15 Gilles Deleuze, “Le devenir révolutionnaire et les créations politiques” in Multitudes, 1990, non paginé.

16 Ibid, 1990, non paginé.

Hamedine Kane, a Senegalese and Mauritanian artist and director, lives and works between Brussels, Paris and Dakar. Through his practice, Hamedine Kane frequents borders, not as signs and factors of impossibility, but as places of passage and transformation, as a central element in the conception of itinerant identity. He uses words and images to highlight the notions of exile, wandering and movement, but also to replace political time with life time. He has developed a strong interest in memory and heritage that is reflected in “The School of Mutants” with Stéphane Verlet-Bottero, a research project that blends past and future, transgressing and irrigating the boundaries of space and time.

Hamedine Kane’s latest works were exhibited at the last Dak’art Biennial curated by Simon Njiami, at Documenta 14: “Every Time A Ear Di Sound”, curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Elena Agudio and Marcus Gammel.

In 2018, his work was the subject of a solo exhibition in Mumbai at the Clark House Initiative, with this structure he continued a collaboration at the Showroom in London. In 2018, Hamedine Kane also exhibited at FIAC, Colonie barrée in Paris and various exhibitions in Brussels, Montreal and France.

He participated in the Taipei Biennale 2020 and the Dak’art and Berlin Biennale 2022.

His film “The Blue House” received a special mention from the jury at the IDFA in Amsterdam in 2020.

Hamedine Kane, artiste et réalisateur sénégalais et mauritanien, vit et travaille entre Bruxelles, Paris et Dakar. À travers sa pratique, Hamedine Kane fréquente les frontières, non pas comme des signes et des facteurs d’impossibilité, mais comme des lieux de passage et de transformation, comme un élément central dans la conception de l’identité itinérante. Il utilise des mots et des images pour mettre en évidence les notions d’exil, d’errance et de mouvement, mais aussi pour remplacer le temps politique par le temps de la vie. Il a développé un intérêt marqué pour la mémoire et le patrimoine qui se reflète dans “The School of Mutants” avec Stéphane Verlet-Bottero, un projet de recherche qui se mêle au passé et au futur, transgressant et irriguant les limites de l’espace et du temps.

Les dernières œuvres de Hamedine Kane ont été exposées lors de la dernière Biennale Dak’art sous la direction de Simon Njiami, à la Documenta 14 : “Every Time A Ear Di Sound”, organisée par Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Elena Agudio et Marcus Gammel.

En 2018, son travail a fait l’objet d’une exposition personnelle à Mumbai à la Clark House Initiative, avec cette structure il a poursuivi une collaboration au Showroom de Londres. En 2018, Hamedine Kane a également exposé à la FIAC, à la Colonie à Paris et différentes expositions à Bruxelles, Montréal et en France. Il a participé à la Biennale de Taipei 2020 et la biennale de Dak’art et de Berlin en 2022.

Son film The Blue House a reçu une mention spéciale du jury à l’IDFA à Amsterdam en 2020.

Valentine Umansky has worked for various institutions dedicated to visual arts and is currently acting as Curator, International Art at Tate Modern. Between 2015 and 2020, she held positions in the U.S. at the International Center of Photography, the Museum of Modern Art and the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. In France, she has collaborated with the Rencontres d’Arles festival, and published Duane Michals, Storyteller (Filigranes). She also co-curated the 2018 LagosPhoto Festival, and Layers. Nigerian Modern Art with Iheanyi Onwuegbucha (CCA, Lagos).

Valentine Umansky a travaillé pour diverses institutions dédiées aux arts visuels et assure actuellement le poste de curatrice pour l’art international, à la Tate Modern de Londres. Entre 2015 et 2020, elle a occupé des postes aux États-Unis à l’International Center of Photography, au Museum of Modern Art et au Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. En France, elle a collaboré avec le festival des Rencontres d’Arles, et a publié Duane Michals, Storyteller (Filigranes). Elle a également été co-commissaire du festival LagosPhoto 2018, et Layers. Nigerian Modern Art avec Iheanyi Onwuegbucha (CCA, Lagos).

”Rayane Mcirdi is an emerging artist, who lives and works in Paris. Inspired by his suburban hometown of Gennevilliers, and popular media ranging from football to American blockbusters, Mcirdi investigates the ways in which media penetrates the collective unconscious in various social and cultural environments.”