My regard on the French art scene is layered by years of misunderstanding. Because what is a scene, because what is a French scene, because nationalism is violent to those who, like myself, are stuck in between places with no hope of legitimately belonging. “Don’t be so Derridean” someone from the back row replies, “an art scene is a context that unifies a set of material tendencies and conceptual questions. These are produced by art, and film, and music schools, and by what is speakable in language in a given place. They are produced by transmission between generations, a kind of filial line of ideas made tangible within a given radius.” But Glissant taught us that filiation justifies conquest, and Derrida taught us that that which is unspeakable structures language, and French art schools did not train Zineb Sedira, who has been chosen to represent France at Venice next year. “You see my difficulty” I say to the young man in the back row.

This list is made up of people who, like myself, belong and do not belong in several places. The selection also reflects a long-term focus of my curatorial practice to establish a dialogue with those who have some relationship to Algeria. This focus comes from my understanding that Algeria remains unspeakable in France, along with everything that happened there. It also comes from my conviction that society is constituted by those who articulate the unspeakable and whose belonging is unstable; those whom society cannot (should not) integrate, not fully, because integration would imply an acceptance of the violence of nationalism. This selection acknowledges the invisible centrality of Algeria’s place in French art and culture, without resolving the impossible contradiction of that fact.

A selection of four artists is a small number to substantiate such a position, I realize. But artwork doesn’t really substantiate theory. Artwork sits next to theory and evolves according to its own logic, sometimes contradicting its framing discourse. It is the possibility of contradiction that allows for any real dialogue, and so perhaps you, dear reader, will take this as an invitation.

[…]

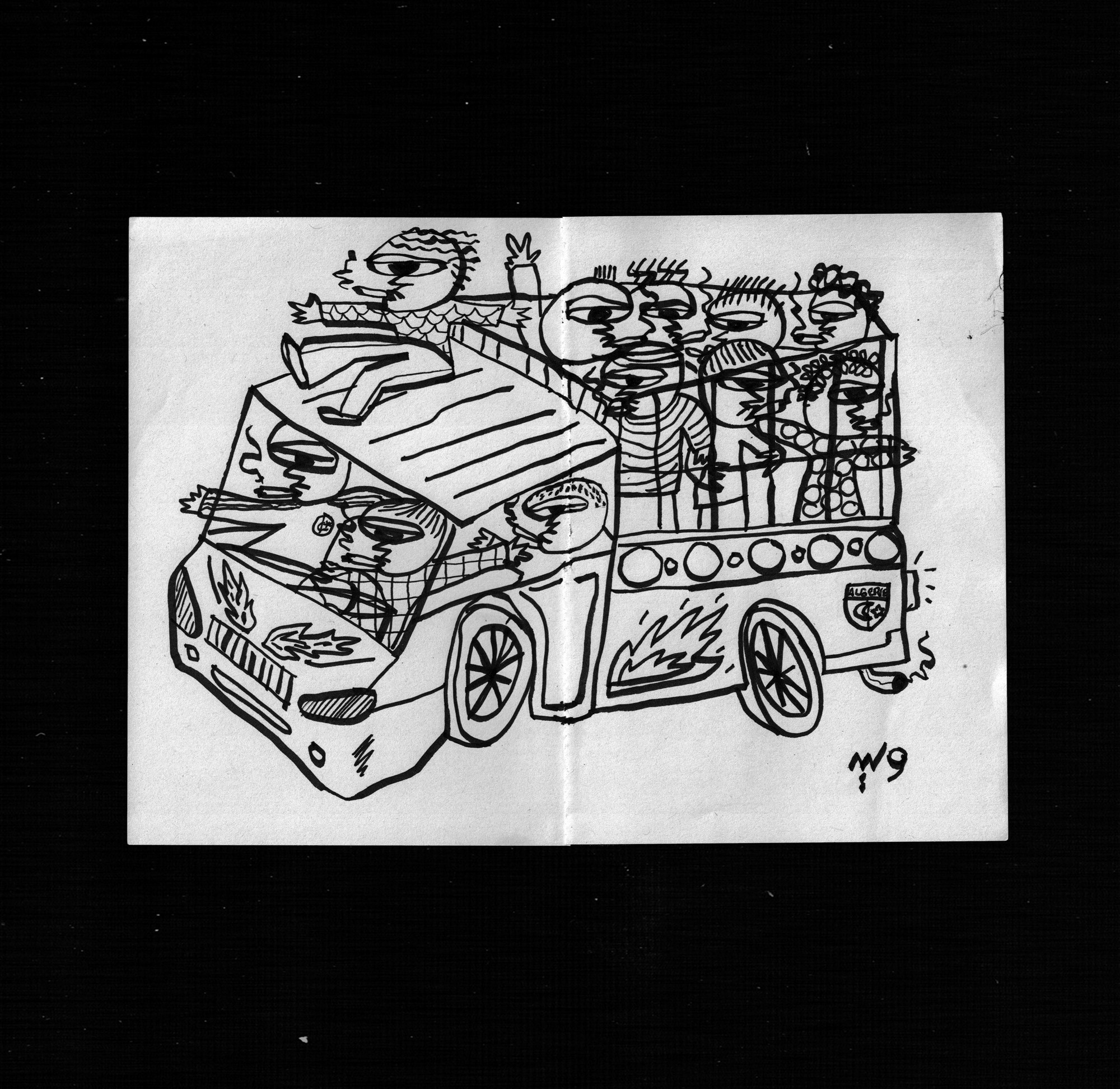

Kho is the central character of Walid Bouchouchi’s series drawings documenting the life of a young Algérois whose world is defined by the rhythm and imaginative universe of the Algerian capital. The best translation of the word «Kho» as Bouchouchi uses it is “bro.” It is a soft word used to acknowledge that every man belongs to someone, to some version of family. As a mode of address, the term also confirms masculinity—Bouchouchi’s Kho could not be a woman.

“Kho is sound, he is a verb, he is profoundly chauvinist and subtly international,” Bouchouchi writes. Kho is born of Bouchouchi’s own observations, but he nevertheless perpetually escapes the limits of an individual experience. Bouchouchi’s corpus of drawings transcribes the slow choreography of Algérois street-life: its semiotic contradictions born of cosmopolitan cultural appropriation, its existence between grapheme and sonic echo.

In one drawing, three cigarette hawkers stand in a line and open their coats to reveal row upon row of Marlboro packs. The careful viewer will notice the reference to Baya’s paintings of houses lining the hills from the mid-20th century. In another drawing, this viewer will see a bird sketched in homage to her perched on the edge of the composition, as though benevolently overseeing the semiotic cacophony of Algérois life. Bouchouchi also borrows Baya’s attention to the shape of the eyes for his figure, along with the implicit suggestion in her work that the act of perception takes up most of a person’s face.

The strength of Bouchouchi’s work lies in his ability to seamlessly layer fine art and street art references, such as sports insignia and popular religious iconography. Kho is the policeman, the street musician, the contemporary Algerian flaneûr all at once. He represents an oral culture composed of “slogans, dictums, and punchlines,” Bouchouchi explains, which are scrawled across the drawings in overlapping lines in Arabic an Imazighen alphabets as well as Latin script. Wordplay and symbolic play converge in the Kho drawings, which stand as a testament to the imaginative virtuosity of a city that remains imperceptible to many beyond its borders.

Natasha Marie Llorens, 2020

Le regard que je porte sur la scène artistique française se présente comme une superposition d’années d’incompréhension. La définition d’une scène, d’une scène française, le nationalisme frappent en effet violemment les personnes qui, comme moi, se trouvent coincées entre plusieurs lieux, sans espoir d’appartenance légitime. « Ne soyez pas si derridienne, ai-je pu entendre au dernier rang. Une scène artistique représente un contexte qui unifie un ensemble de tendances matérielles et de questions conceptuelles. Celles-ci sont produites par les écoles d’art, de cinéma et de musique et par ce qui est dicible dans le langage à un endroit donné. Elles sont produites par la transmission de génération en génération, une sorte de lignée d’idées qui se concrétisent au sein d’un périmètre spécifique. » Edouard Glissant nous a toutefois enseigné que la filiation justifie la conquête, alors que Derrida nous a appris que l’indicible structurait le langage, et les écoles d’art françaises n’ont pas formé Zineb Sedira, qui a été choisi pour représenter la France à Venise l’an prochain. « Vous comprenez mon problème », ai-je répondu au jeune homme du dernier rang.

Cette liste est constituée de personnes qui, comme moi, se sentent à la fois légitimes et illégitimes à différents endroits. Une telle sélection reflète également un objectif sur le long terme de mon activité de commissaire d’exposition visant à établir un dialogue avec quiconque entretient des liens avec l’Algérie. Je poursuis cette quête dans la mesure où je comprends que l’Algérie, ainsi que tous les événements qui s’y sont produits demeurent indicibles en France. Elle me vient également de ma conviction selon laquelle la société est façonnée par celles et ceux qui articulent l’indicible et dont l’appartenance est instable, celles et ceux que la société ne peut (ne doit) pas intégrer, pas entièrement, car l’intégration impliquerait une acceptation de la violence du nationalisme. Cette sélection reconnaît la place centrale invisible que l’Algérie occupe dans la culture et l’art français, sans pouvoir résoudre l’impossible contradiction de ce fait.

Je me rends compte qu’avoir choisi quatre artistes est un peu limité pour justifier une telle position. Mais l’œuvre d’art ne vient pas vraiment étayer la théorie. Elle se tient à côté de cette dernière et évolue selon sa propre logique, quitte à parfois contredire le discours qui l’encadre. Cette possibilité de contradiction permet d’entamer un vrai dialogue que vous, chers lecteurs, prendrez peut-être pour une invitation.

[…]

Kho constitue le personnage central de la série de dessins de Walid Bouchouchi qui illustrent la vie d’un jeune Algérois dont le monde se définit par le rythme et l’univers créatif de la capitale algérienne. Le mot « Kho » tel qu’employé par l’artiste peut se traduire de la meilleure façon par « frère ». Ce terme affectueux s’utilise pour reconnaître à chaque homme son sentiment de rattachement à une personne, à une famille. Sa forme confirme également la notion de masculinité qu’elle implique (le Kho de Walid Bouchouchi ne peut pas être une femme).

« Kho est un mot pertinent, un verbe puissant. Son chauvinisme profond n’a d’égal que sa subtile connotation internationale », écrit l’artiste. Ce terme a vu le jour grâce aux propres observations de ce dernier, mais il échappe toutefois perpétuellement aux limites d’une expérience individuelle. Le corpus de croquis transcrit la lente chorégraphie de la vie urbaine d’Alger : ses contradictions sémiotiques issues de l’appropriation culturelle cosmopolite, son existence entre graphème et écho sonique.

L’un des dessins montre trois marchands ambulants de cigarettes qui se tiennent debout en file indienne et ouvrent leurs manteaux pour dévoiler des rangées successives de paquets de Marlboro. Un œil avisé remarquera la référence aux maisons alignées sur les collines des tableaux de Baya datant du milieu du XXe siècle. Sur une autre création, il verra un oiseau croqué en son hommage, perché au bord de la composition, qui semble surplomber avec bienveillance la cacophonie sémiotique de la vie algéroise. Walid Bouchouchi emprunte également à cette peintre l’importance de la forme des yeux pour son illustration, ainsi que la suggestion implicite dans son œuvre selon laquelle l’acte de perception occupe la plus grande partie du visage d’une personne.

La force des travaux de cet homme réside dans sa capacité à superposer aisément les beaux-arts et les références à l’art urbain comme les emblèmes sportifs et l’iconographie religieuse populaire. Kho incarne à la fois le policier, le musicien de rue et le flâneur algérien contemporain. Il symbolise une culture orale composée de « slogans, dictons et punchlines », tagués sur les dessins telles des lignes qui se chevauchent en alphabets arabe et berbère, ainsi qu’en caractères latins, comme l’explique Walid Bouchouchi. Jeux de mots et symbolique convergent dans les dessins de Kho, ce qui témoigne de la virtuosité imaginative d’une ville qui demeure imperceptible à bien des personnes au-delà de ses frontières.

Natasha Marie Llorens, 2020

Traduit de l’anglais par Elsa Maggion

Born in Algiers, where he later graduated from the School of Fine Arts, Walid currently lives in Marseille, and works between Paris, Marseille and Algiers. His recent work is mainly pictorial and gives a glimpse of urban popular culture in the streets of Algiers through which “kho”, his main character, slips.

Walid has participated in various exhibitions, including the 2014 Dak’art Dakar biennial off, the Museum of african design MOAD in Johannesburg in 2015, DUBAI design week in 2016 and 2017. He has also been included in the following publications: Houcine Zaourar in 2014, Algeria unveiled from shadow to light, Algeria: The nahda of letters, the rebirth of words in 2015 and Sex, race & colonies in 2018.

Né à Alger, où il est ensuite diplômé de l’école des beaux-arts, Walid vit actuellement à Marseille, et travaille entre Paris, Marseille et Alger. Son travail récent est principalement pictural et donne un aperçu de la culture populaire urbaine dans les rues d’Alger à travers lesquelles ” kho “, son personnage principal, se glisse.

Walid a participé à différentes expositions, notamment au off de la biennale Dak’art Dakar 2014, au Museum of african design MOAD à Johannesburg en 2015, à la DUBAI design week en 2016 et 2017. Il a également fait partie des publications suivantes : Houcine Zaourar en 2014, l’Algérie dévoilée de l’ombre à la lumière, Algérie : La nahda des lettres, la renaissance des mots en 2015 et Sex, race & colonies en 2018.

Natasha Marie Llorens is a Franco-American independent curator and writer. Recent curatorial projects include Waiting for Omar Gatlato: A Survey of Contemporary Art from Algeria and Its Diaspora at the Wallach Art Gallery and The Wall at the End of the Rainbow at the Jan van Eyck Academie. Llorens also edited the first English-language anthology of writing on Algerian and Franco-Algerian aesthetics and art history, co-published by Sternberg Press. She is in residence at the Jan van Eyck Academie and a core tutor in History & Theory at Piet Zwart.

Natasha Marie Llorens est une commissaire d’exposition indépendante et une écrivaine franco-américaine. Ses projets récents dans son domaine incluent Waiting for Omar Gatlato: A Survey of Contemporary Art from Algeria and Its Diaspora à la Wallach Art Gallery et The Wall at the End of the Rainbow à la Jan van Eyck Academie. Elle a également rédigé le premier ouvrage d’anthologie en anglais sur les esthétiques et l’histoire de l’art algériennes et franco-algériennes, copublié par Sternberg Press. Actuellement en résidence à la Jan van Eyck Academie, elle enseigne également l’histoire et la théorie au Piet Zwart Institute.

Kameli is not only interested in deconstructing the existing image archive, she also insists on the presence of a counter-archive, one less public but nevertheless crucial. She renders visible women who themselves produced representations, such as: Louisette Ighilahriz, and an FLN militant who recruited women to sew Algerian flags for the Independence Day celebration; Louiza Ammi Sid, who worked throughout the Black Decade as a photojournalist; Marie-José Mondzain, a French philosopher of the image born in Algiers whose motherwas from a well-established Jewish Algerian family and whose father was a Polish artist, a communist who escaped the Holocaust; and the first Algerian female filmmaker andnovelist, Assia Djebar.