The exhibition Fluid Desires at art institute Nest in the Hague, the Netherlands, ended on March 22. Of the eight participating artists, five were French. That’s no coincidence. As a Dutch liaison in Paris, I like to create connections between France and the Netherlands. Two countries that are geographically practically neighbors but at the same time, culturally and linguistically, worlds apart. They seem to be each others blind spot whereas the exchange can be, and has proven, to be so fruitful.

I started the research for Fluid Desires in 2013 when I was still living in the Netherlands and continued it in France. At the time it struck me that many artists used liquids. This intrigued me and I was wondering what motivated them. While researching I discovered a wider and more interesting field of art that deals with fluidity without necessarily using liquids, among them some of my favourite French artists: Hicham Berrada, Mimosa Echard, Marie Maillard, Shanta Rao and Jérôme Robbe (apart from Inge van Genuchten, Maya Rochat and Leonid Tsvetkov). I had been following their work for years. None of them had explored Dutch territory before. Now that the exhibition has just happened, visitors were glad to discover them and shared my enthusiasm.

Fluid Desires was an exhibition about the current liquid world. Concepts that have been carved in stone for decades are shifting. Think for example of time, space, reality, nature, object and the object-human relationship. Developments in science, technology and philosophy are the catalyst for these changes. An important place occupies the Polish-British sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman who has extensively analysed the increasingly slippery society. The hybrid, unstable world serves as a point of departure for the artists in Fluid Desires. Post-apocalyptic cocktails and other works of art with a liquid allure zoom in on blurring boundaries between natural and synthetic, living and non-living. Their understanding of the world is through matter. The artworks do not use symbols or metaphors, nor do they depict anything; on the contrary, they just are. These explosions of color, texture, and slipperiness, are related in aesthetics. Throughout the exhibition, the concept of contagion is recurrent. Contamination as a marker for meanings that mix, images that merge and ideas that influence each other. The exhibition has sometimes science-fiction-like traits as platitudes are deserted and the future is fantasized.

[…]

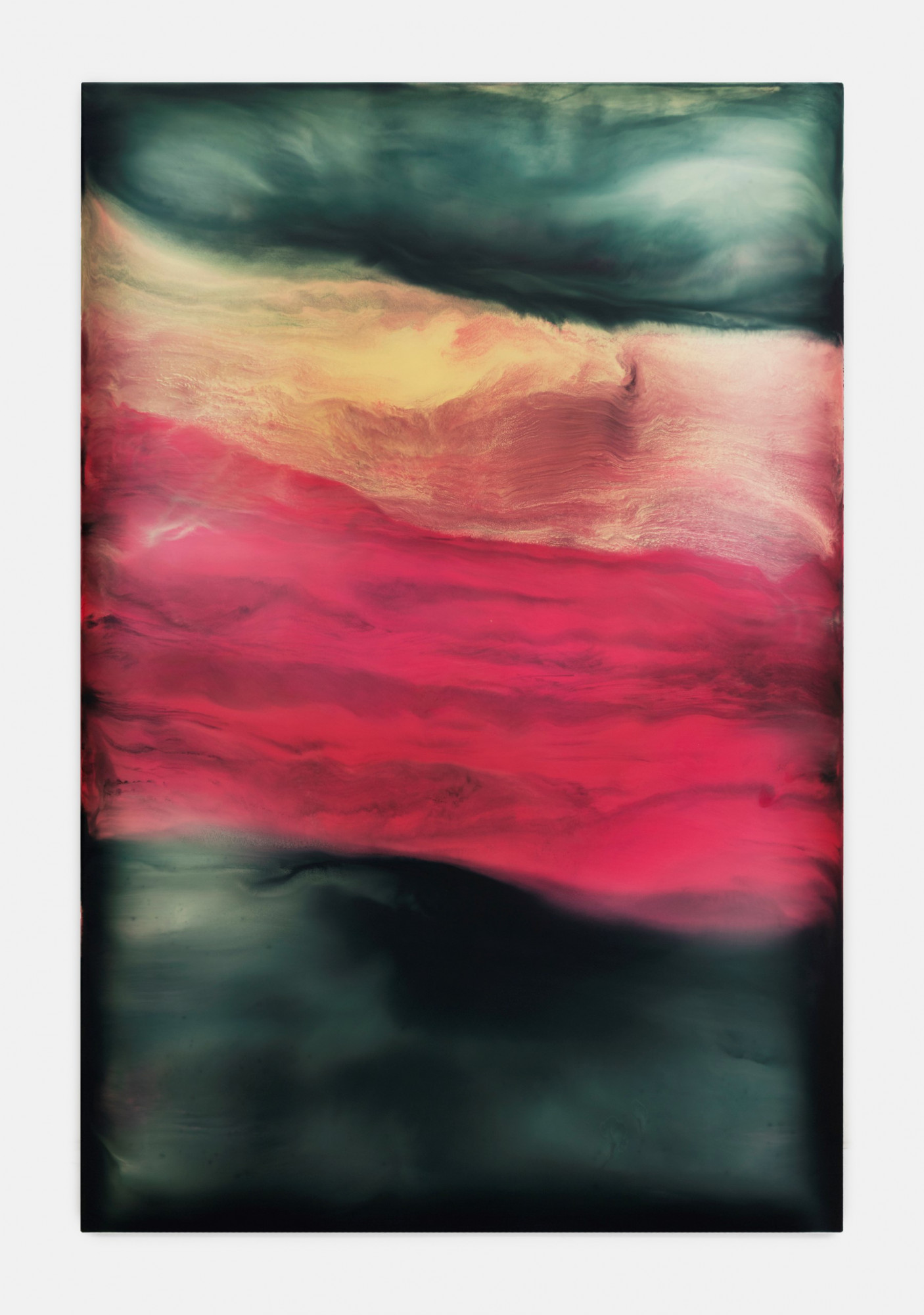

A striking statement by Jérôme Robbe is: “Painting has nothing to do with genius, but everything with inventions. The genius lies in inventing materials and techniques that make it possible to paint differently and better.” The artist therefore regards the history of painting as a succession of technical inventions. In order to proceed the development of painting and to be a painter of your time, it is necessary to continue the sequence of inventions. The L’Air de Rien series, started around 2009-2010, for example, is painted on plexiglass with a silver or gold coating which effects the depth, brightness and temperature of the applied color. The series responds to the aesthetics of body work of cars, gems and jewellery, but also digital devices.

Furthermore, in this and other series Jérôme Robbe drives the liquid aspect of painting to the forefront and makes it the essence of the work. He lets the paint flow freely and creates an image that contains an immense temporality. The paintings from the series L’Air de Rien and Surfaces are evocations of a fluid world. It seems as if paint and support have briefly solidified before the paint continues to drip, curve and flow. For Robbe, fluidity represents freedom. He doesn’t want to control the creative process but prefers letting things run their course and to leave things to drift. Not one sketch precedes these paintings. It arises in the here and now by anticipating what happens with the material.

The paintings in the L’Air de Rien series are the result of an elaborate process in which fluidity plays an important role. The initial step is warming the plexiglass with a heat gun. This results in it becoming soft; expanding; forming bubbles and ripples; and, craquelure appearing on the surface. Subsequently the artist vaporizes several liters of water above the plexiglass sheet that is lying flat. The mist slowly whirls down on the panel. Transparent varnish, colored with pigments, is then poured on and allowed to find a way across the distorted surface, just as a river follows its bed or as a lava flow searches its lowest point. Gravity and chance do their job. Depending on the result, certain parts are sanded lighter (for example, where too much varnish accumulates) and once again poured with matte or glossy varnish. Because of the consistent application of a lateral line onto the canvas, the abstract monochromes can also be recognized as landscapes. Where the artist previously depicted landscapes, he nowadays lets them emerge.

When I visited Jérôme Robbe’s studio a few times in 2019, it was still based at a stone’s throw of Paris, in the northern banlieue Asnières-sur-Seine. The former printing house was shared with many other artists including Mohammed Bourouissa. His studio, consisting of a working area and a ‘showroom’, was bustling with activity. Paintings from four series, if I counted correctly, were at different stages of completion. Two paintings from the Surfaces series were drying in the varnish booth. A great, intoxicating fragrance oozed towards me. The cardboard on the floor soaked up the excess paint. It gave the artist the idea for yet another series of paintings: Diary (Beyond the subject lies time) tells the history of the studio.

The Surfaces and L’Air the Rien series have many similarities. A thin sheet of plexiglass functions as the support and instead of depicting a landscape it is created by pouring the material on the surface. It reminds the artist of Californian skies. However, in the Surfaces series the plexiglass sheet is glued to an aluminum frame. As the bars of this frame have a visual effect on the front, the artists plays with the amount and positioning of these bars. For example, a black painting has a classic cross shape on the back and a blue painting is divided into six sections. Layers of the cast varnish are removed by sanding and this creates bright spots or areas. In fact, the whole point of these abstract paintings seems to be to create a surface on which light has free rein. Often another layer of varnish is poured on it, again followed by sanding. A process that is repeated several times. The method seems to be very controlled, however it is rather a secession of accidents and material constraints. The Light and Paint series seems to be a sequel to this. Neutral colored canvas is inlaid with one or two rectangular color panels. These often huge but light paintings clearly pay homage to Mark Rothko.

Nanda Janssen, 2020

L’exposition Fluid Desires présentée à la galerie Nest à La Haye, aux Pays-Bas, s’est terminée le 22 mars. Parmi les huit artistes participants, cinq étaient français. Ce n’est pas un hasard. En tant que néerlandaise chargée de mission à Paris, j’aime créer des liens entre la France et les Pays-Bas. Deux pays presque voisins, mais des mondes à part du point de vue culturel et linguistique. Ils semblent être la zone grise l’un de l’autre alors que l’échange peut être, et s’est avéré, si fructueux.

J’ai commencé les recherches pour Fluid Desires en 2013 alors que je vivais encore aux Pays-Bas et je les ai poursuivies en France. À l’époque, j’ai été frappé par le fait que de nombreux artistes utilisaient des liquides. Cela m’intriguait et je me demandais ce qui les motivait. Au cours de mes investigations, j’ai découvert un domaine de l’art plus large et passionnant qui s’intéresse à la fluidité sans nécessairement utiliser de liquides, et où officient certains de mes artistes français préférés : Hicham Berrada, Mimosa Echard, Marie Maillard, Shanta Rao et Jérôme Robbe (sans oublier Inge van Genuchten, Maya Rochat et Leonid Tsvetkov). Je suivais leur travail depuis des années. Aucun d’entre eux n’avait exploré le territoire néerlandais auparavant. Lors de l’exposition, les visiteurs ont été enchantés de les découvrir et ont partagé mon enthousiasme.

Fluid Desires était une exposition consacrée au monde liquide actuel. Des concepts gravés dans la pierre depuis des décennies sont en train de changer. Pensez par exemple au temps, à l’espace, à la réalité, à la nature, à l’objet et à la relation objet-homme. L’évolution de la science, de la technologie et de la philosophie est le catalyseur de ces changements. Une place importante de la recherche dans ce domaine revient au sociologue et philosophe polono-britannique Zygmunt Bauman, qui a analysé en détail une société de plus en plus instable. Le monde hybride et fluctuant sert de point de départ aux artistes de Fluid Desires. Les cocktails post-apocalyptiques et autres œuvres d’art à l’apparence liquide mettent en lumière les frontières floues entre le naturel et le synthétique, le vivant et le non-vivant. Les artistes appréhendent le monde à travers le prisme de la matière. Les œuvres d’art n’utilisent ni symboles ni métaphores, et ne dépeignent rien ; elles sont, tout simplement. Ces explosions de couleurs, de textures et l’instabilité qu’elles suggèrent sont liées à l’esthétique. Le concept de contagion est récurrent tout au long de l’exposition. La contagion agit comme marqueur de significations qui se mélangent, d’images qui fusionnent et d’idées qui s’influencent mutuellement. L’exposition prend parfois des allures de science-fiction, car elle se départit des lieux communs et fantasme l’avenir.

[…]

Jérôme Robbe déclare : « La peinture n’a rien à voir avec le génie, mais plutôt avec les inventions. Le génie consiste à inventer des matériaux et des techniques qui permettent de peindre autrement et mieux. » L’artiste considère donc l’histoire de la peinture comme une succession d’inventions techniques. Pour poursuivre le développement de la peinture et être un peintre de son temps, il est nécessaire de poursuivre les inventions. Les travaux de la série de L’Air de Rien, entamée vers 2009-2010, par exemple, sont réalisés sur du plexiglas avec une couche d’argent ou d’or qui affecte la profondeur, la luminosité et la « température » de la couleur appliquée. Cette série obéit à l’esthétique de la carrosserie des voitures, des pierres précieuses et des bijoux, mais aussi des appareils numériques.

Dans cette série comme dans d’autres, Jérôme Robbe met en avant l’aspect liquide de la peinture et en fait l’essence même de l’œuvre. Il la laisse couler librement et crée une image à l’immense temporalité. Les œuvres des séries L’Air de Rien et Surfaces sont des évocations d’un monde fluide. Peinture et support semblent s’être brièvement solidifiés avant que la peinture ne continue à dégouliner, sinuer et se répandre. Pour Jérôme Robbe, fluidité est synonyme de liberté. Il se refuse à contrôler le processus de création et préfère laisser les choses suivre leur cours, les laisser dériver. Il ne réalise aucune esquisse. L’œuvre naît dans l’ici et maintenant en anticipant les réactions de la matière.

Les peintures de la série L’Air de Rien résultent d’un processus élaboré dans lequel la fluidité joue un rôle important. L’étape initiale consiste à chauffer le plexiglas à l’aide d’un pistolet thermique. Le plexiglas ramollit, se dilate, forme des bulles et des ondulations, et des craquelures apparaissent à la surface. L’artiste vaporise ensuite plusieurs litres d’eau sur la feuille de plexiglas posée à plat d’où il se dégage de la vapeur qui se met à tourbillonner lentement. Il verse ensuite un vernis transparent, coloré avec des pigments, et le laisse se frayer un chemin sur la surface déformée, comme une rivière suit son lit ou une coulée de lave se répand sur le flanc du volcan jusqu’au point où elle se solidifie. La gravité et le hasard font leur travail. En fonction du résultat, il ponce légèrement certaines parties (par exemple, là où trop de vernis s’accumule) et applique à nouveau un vernis mat ou brillant. En raison de la présence constante d’une ligne horizontale sur le support, les monochromes abstraits peuvent évoquer des paysages. Là où l’artiste représentait auparavant des paysages, il les laisse aujourd’hui émerger.

Nanda Janssen, 2020

Traduit de l’anglais par Elsa Maggion

Born in Paris in 1981, Jérôme Robbe lives and works between Paris and the west coast of France. A 2008 graduate of the Villa Arson in Nice, Jérôme Robbe regularly exhibits in French and international galleries. His work is also presented and collected by art centers such as the Mac/Val in Vitry-sur-Seine or the Nest art center in La Hague, Netherlands. He collaborates internationally with various exhibition curators allowing the circulation of his works from Sydney to London, through Los Angeles and New York. A canvas to immerse oneself in as in a landscape, to survey, to watch in its infinite changes. A painting of possibilities. This is how Jérôme Robbe’s practice could be defined; to reinvent his medium. Heir to American Abstraction and its vast all-over horizons, but also to German Romanticism and its sense of the sublime, he always juggles with the painting as with a landscape in itself; “I began by painting skies, and little by little I freed myself from this origin, to go towards the sensation, the feeling”. Fascinated by the constant invention of the Renaissance, he continually imagines new tools. Everything in his work participates in this enterprise of deconstructing painting to build surfaces. Jérôme Robbe has worked a lot with mirror surfaces. What he seeks in each painting is a meaningful and reconciling image. Because the question that the painting of Jerome Robbe poses, beyond a henceforth classic questioning of the means of the painting, is rather that of the place of the observer. Where do we stand when we look at a painting?

Né à Paris en 1981, Jérôme Robbe vit et travaille entre Paris et la côte Ouest de la France. Diplômé de la Villa Arson à Nice en 2008, Jérôme Robbe bénéficie régulièrement d’expositions au sein de galeries françaises et internationales. Son travail est également présenté et collectionné par des centres d’arts tel que la Mac/Val à Vitry-sur-Seine ou le centre d’art Nest à La Hague au Pays Bas. Il collabore à l’international avec divers commisssaires d’expositions permettant la circulation de ses oeuvres de Sydney à Londres, en passant par Los Angeles et New-York. Une toile où s’immerger comme en un paysage, à arpenter, à surveiller dans ses infinis changements. Une peinture des possibles. C’est un peu de la sorte que pourrait se définir la pratique de Jérôme Robbe qui n’a de cesse de réinventer son médium. Héritier de l’abstraction américaine et de ses vastes horizons en all-over, mais aussi du romantisme allemand et de son sentiment de sublime, il jongle toujours avec le tableau comme avec un paysage en soi. « J’ai commencé en peignant des ciels, et peu à peu je me suis dégagé de cette origine, pour aller vers la sensation, le sentiment ». Fasciné par l’invention constante de la Renaissance, il imagine continuellement de nouveaux outils. Tout participe chez lui à cette entreprise de déconstruction de la peinture pour bâtir des surfaces. Jérôme Robbe a beaucoup travaillé avec des surfaces miroir. Ce qu’il cherche dans chaque tableau, c’est une image signifiante réconciliante. Car la question que pose la peinture de Jérôme Robbe, au delà d’une désormais classique interrogation des moyens de la peinture, est plutôt celle de la place du regardeur. Où se situe-t-on quand on regarde un tableau?

Being an art historian, Nanda Janssen works as an independent curator and art critic. She is also Councellor of visual arts for the Embassy of the Netherlands in France since 2018. She considers herself as a Dutch liaison in Paris. Since 2007 she has specialized in the Paris and French contemporary art circuit. After two residencies of a year at La Cité Internationale des Arts, the last of which ended in 2017, she decided to stay in Paris. She publishes amongst others in the Dutch art magazines Museumtijdschrift, Metropolis M, See All This and the Belgian magazine Hart. Nanda Janssen curated the exhibitions Fluid Desires (Nest, The Hague, 2020), Eva Nielsen (Selma Feriani Gallery, Tunis, 2017), Bruno Peinado (21rozendaal, Enschede) and Carried-Away - Procession in Art (Museum Arnhem). Furthermore, she proposed the Ceija Stojka exhibition from La Maison Rouge in Paris to the Dutch museum Het Valkhof and subsequently assisted the French curators (2019). In addition, she will be on the committee ‘mécénat’ of La Fondation des Artistes (2022-2023). She was one of the jury members of the Royal Award for Dutch Painting (2014-2019), initiated by HM King Willem-Alexander, and committee member visual arts of the Dutch Council for Culture (2015-2017), the legal adviser of the government in the fields of the arts, culture and media.

Historienne de l’art, Nanda Janssen travaille en tant que commissaire d’exposition et critique d’art indépendante. Conseillère en arts visuels pour l’ambassade des Pays-Bas en France depuis 2018, elle se considère comme une liaison néerlandaise à Paris. Depuis 2007, elle est spécialisée dans le circuit de l’art contemporain parisien et français. Après deux résidences d’un an à La Cité Internationale des Arts, dont la dernière s’est terminée en 2017, elle s’installe à Paris. Elle publie entre autres dans les magazines d’art néerlandais Museumtijdschrift, Metropolis M, See All This et le magazine belge Hart. Elle a été commissaire des expositions Fluid Desires (Nest, La Haye, 2020), Eva Nielsen (Galerie Selma Feriani, Tunis, 2017), Bruno Peinado (21rozendaal, Enschede) et Carried-Away - Procession in Art (Museum Arnhem). En outre, elle a proposé l’exposition Ceija Stojka de La Maison Rouge à Paris au musée néerlandais Het Valkhof et a ensuite assisté les commissaires français (2019). Elle fera partie du comité “mécénat” de la Fondation des Artistes (2022-2023). Nanda Janssen a été l’un des membres du jury du Prix royal de la peinture néerlandaise (2014-2019), initié par SM le Roi Willem-Alexander, et membre du comité des arts visuels du Conseil néerlandais pour la culture (2015-2017), le conseiller juridique du gouvernement dans les domaines des arts, de la culture et des médias.

Jérôme Robbe drives the liquid aspect of painting to the forefront and makes it the essence of the work. He lets the paint flow freely and creates an image that contains an immense temporality.