VERA MOLNAR

Throwing dice

Making art is a lot about identifying problems, seeking solutions and making choices. Often, all of these are equally hard to do, so let’s challenge the triad with a little dice game: Throwing dice can either be taken literally, as a set of dice, dot-painted on their six square surfaces, thrown into the air, whirring, dancing around each other, hitting a surface, cutting the edge and revealing their final face. Or – as in this text – it can be a synonym for an approach to art that uses a tool or machine- be it scientific or serendipitous, systematic or playful. Either way: Throwing dice may seem like a harmless and joyful experience but at the same time, the delegation of work to another entity causes discussion, shaking the concept and role of an artist, the creative process behind an artwork and the role of a singular work.

Problems and solutions

The concrete painter and computer art pioneer Vera Molnar (1924 in Budapest, lives in Paris) has used systems and randomness since the early stages of her artistic practice, in a process that she claims to include “1% of (dis)order”. Her mostly serial work is based on variations of geometric shapes and arrangements with changing parameters: drawings from a single line, concentric squares and grids. Already in an early series of paintings from her teenage times that was unfortunately lost, she created her first artistic problem-solution-complex. She had repeatedly painted the sunset at lake Balaton with just some lines and a circle, using a set of pastels. In order not to rub down some pastels more than others, she had worked with a system taking color turns - always putting the last used color to the back until the first color came first in line again.

From 1958, she started creating work with her so-called „machine imaginaire“, referring to a variety of methods, including throwing dice in order to find a grammar of formal variations. In 1968 she was among the first artists to explore the power of computation, creating algorithmic drawings at Sorbonne University Computing Center in Orsay. Back then, the computer without screen was quite a black box, working on punch cards with binary 0-1 codes. First invented for Jacquard looms in the early 19th century, punch cards translate textile patterns or any other codable production process into simple yes or no commands („hole“ or „no hole“ meaning „warp up“ or „warp down“ in a loom). I imagine this work method must have created an interesting lack of immediacy for Vera Molnár, giving rise to a sense of virtuality - a distance between the artist, her imagined creation and the physical work. The waiting time for the result must have provided space for surprises and coincidence, not unlike working in a dark room.

Making choices: An artist and her body

A line is the record of a movement, a force that is generally attributed to the artist, who combines mind and body in one entity. However, in a social model like Vera Molnár’s human-dice or human-machine collaboration, this entity might be split up: A „mind 1“ and „body 0“, or „mind 0“ and „body 1“ situation could be created, and the machine could take over the task of the one or the other, whichever the human refuses to provide. A line would then be drawn by a plotter according to a human command or the other way around: a decision would be taken by a system and the artist fulfills it in a drawing. The game of sharing tasks broadens the artistic possibilities and yet also narrows down the field by defining a very specific set of rules. So, collaborating with a machine can provide liberation, even if it won’t liberate the artist from making choices after all. „What is so thrilling to experience is not only the stepwise approach toward the envisioned goal but also sometimes the transformation of an indifferent version into one that I find aesthetically appealing.“ (Vera Molnar, Toward aesthetic guidelines for painting with the aid of a computer, 1975)

Making friends with machines

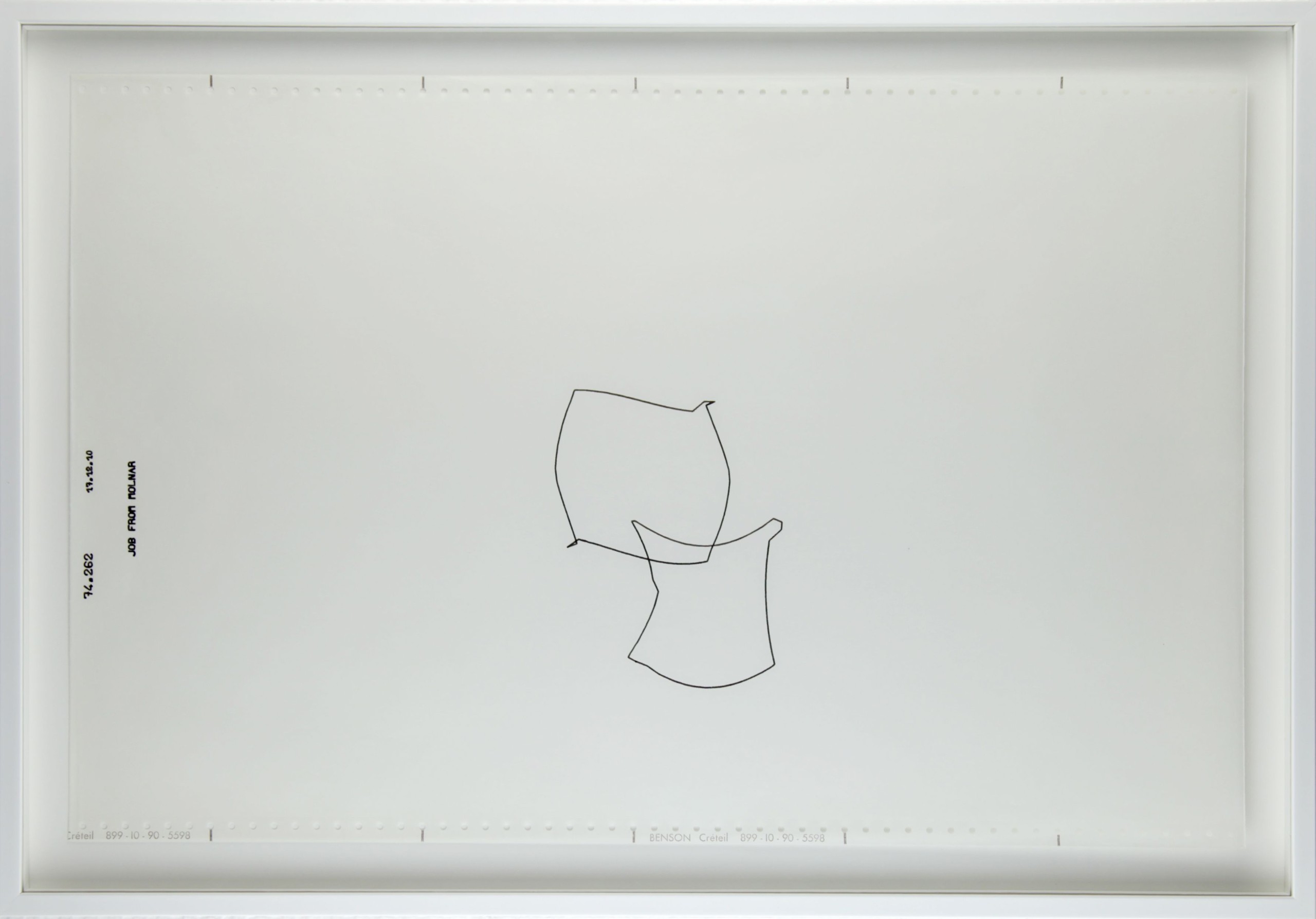

The first precursor of a computer was the “analytical engine” (1837), an automatic calculation machine that was supposed to autonomously solve the mathematical problems it was given. A group of people had dedicated their life to it, but the machine was considered a failure and was never built. I read Vera Molnár’s series of drawings Love Story (1974) as an hommage to the marriage between a machine and a human. And potentially, as retrospective support or a love letter to Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), the British programming pioneer who was the only woman involved in the “analytical engine” and who wrote the world’s first piece of software for it in 1843. Some 130 years later, Vera Molnar’s own tedious work process at the Sorbonne’s Computing Center could only be completed when the scientists were off duty, in the evening or weekends. “From Love Stories, I did a lot because there was a strike or something. I was alone, it was joyful. “, she remembers in a recent interview (Vera Molnar in conversation with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, 2018).

Love Story is a poetic depiction of a sometimes smooth, sometimes complicated communication between two entities: The two squares overlap, they are distorted, in crisis, meet up again, split up, get back together. They curse each other, they love each other, they are in dissent and in harmony, they give each other orientation on the page. Maybe they are also a portrait of two dice thrown into the air.

Jeter les dés

La création artistique s’apparente en grande partie à identifier des problèmes, à chercher des solutions et à faire des choix. Cela se traduit souvent par une même difficulté. Alors, défions cette triade avec un petit jeu de dés : jeter les dés peut être pris au sens littéral, comme un ensemble de dés avec des points peints sur leurs six surfaces carrées qui sont lancés en l’air, tourbillonnent, dansent les uns autour des autres, heurtent une surface, basculent et révèlent leur face finale. Ou, comme dans ce texte, cela peut être synonyme d’une approche de l’art qui s’appuie sur un outil ou une machine – peu importe que ce dispositif soit scientifique ou fortuit, systématique ou ludique. Selon ce principe, jeter les dés peut sembler une expérience inoffensive et joyeuse. Mais en même temps, le fait de déléguer une tâche à une autre entité suscite la réflexion en bouleversant la conception de l’artiste et de son rôle, le processus créatif qui se dissimule derrière une œuvre et la fonction d’une création singulière.

Problèmes et solutions

L’artiste Vera Molnar (née en 1924 à Budapest et vivant à Paris), figure de l’abstraction concrète et pionnière de l’art numérique, utilise les systèmes et le hasard depuis les débuts de sa pratique artistique, dans un processus qui, selon elle, comprend « 1% de (dés)ordre ». Son travail, le plus souvent sériel, est basé sur des variations de formes géométriques et des dispositifs aux paramètres changeants : dessins effectués à partir d’une seule ligne, carrés concentriques, grilles. Déjà, dans une série de peintures précoces datant de sa jeunesse et malheureusement perdues, elle créé son premier ensemble artistique qui l’amène à définir des contraintes auxquelles elle apporte des solutions en peignant plusieurs versions d’un même coucher de soleil au bord du lac Balaton uniquement à partir de quelques lignes et d’un cercle, en utilisant un jeu de pastels. Afin de ne pas user certains pastels plus que d’autres, elle institue un système de rotation des couleurs, replaçant systématiquement la dernière couleur utilisée derrière les autres jusqu’à ce que la première soit, à la fin, à nouveau placée en tête de la rangée de pastels.

À partir de 1958, elle commence à créer des œuvres avec ce qu’elle appelle sa « machine imaginaire ». Elle se réfère à une grande variété de procédés, dont le lancer de dés, afin d’élaborer une grammaire de variations formelles. En 1968, elle fait partie des premiers artistes à explorer le pouvoir de l’informatique, en produisant des dessins algorithmiques au centre informatique de l’université de la Sorbonne à Orsay. À cette époque, l’ordinateur sans écran est pour l’essentiel une boîte noire fonctionnant avec des cartes perforées et des codes binaires 0-1. Inventées pour les métiers Jacquard au début du XIXe siècle, les cartes perforées traduisent les motifs textiles ou tout autre processus de production codable en simples instructions « oui » ou « non » (la présence d’un trou, dans le métier à tisser, signifiant que le fil de chaîne reste en place, son absence signifiant que le fil descend). Je suppose que cette méthode de travail a dû créer un manque d’instantanéité intéressant pour Vera Molnar, donnant lieu à une sensation de virtualité et créant, de ce fait, une distance entre l’artiste, sa création imaginaire et l’œuvre matérielle. Le temps d’attente du résultat laissait sans aucun doute de la place pour les surprises et les coïncidences, un peu comme lorsqu’on travaille dans une chambre noire.

Faire des choix : une artiste et son corps

Une ligne est l’enregistrement d’un mouvement, une force qui est généralement attribuée à l’artiste, lequel associe l’esprit et le corps en une seule et même entité. Toutefois, dans un système de relations tel que la collaboration « homme-dés » ou « homme-machine » de Vera Molnar, cette entité peut être divisée : il est possible de créer une configuration binaire (« esprit-1 » et « corps-0 », ou « esprit-0 » et « corps-1 »), sachant que la machine peut prendre en charge la tâche de l’un ou de l’autre, quelle que soit celle que l’être humain refuse d’assurer. Ainsi, une ligne peut être dessinée par un traceur exécutant une instruction programmée par l’être humain, et inversement, une décision peut être prise par un système que l’artiste s’applique ensuite à exécuter dans un dessin. Ce jeu fondé sur un partage des tâches élargit les possibilités artistiques mais il en restreint aussi le champ en définissant un ensemble de règles très précises. Ainsi, collaborer avec une machine peut être libérateur, même si, en fin de compte, l’artiste n’est pas libérée de l’obligation de faire des choix. « Ce qui est si excitant à expérimenter, c’est non seulement l’approche progressive vers l’objectif visé, mais aussi, dans certains cas, la transformation d’une version neutre en une version que je trouve esthétiquement intéressante. » (Vera Molnar, Toward aesthetic guidelines for painting with the aid of a computer , 1975)

Sympathiser avec la machine

Le premier précurseur de l’ordinateur fut la « machine analytique » (1837), une machine permettant de réaliser automatiquement un calcul et conçue pour résoudre de manière autonome les problèmes mathématiques qu’on lui soumettait. Quelques personnes y consacrèrent leur existence, même si cette machine fut considérée comme un échec et ne fut jamais construite. J’interprète la série de dessins de Vera Molnar intitulée Love Story(1974) comme un hommage à l’alliance entre la machine et l’être humain – et, peut-être, comme un soutien rétrospectif, ou une déclaration d’amour, à Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), la pionnière britannique de la programmation informatique. Seule femme impliquée dans la conception de la « machine analytique », elle écrivit à son intention, en 1843, le premier programme informatique au monde. Quelque 130 ans plus tard, le travail fastidieux de Vera Molnar au centre informatique de la Sorbonne ne peut être effectué qu’en dehors des heures de service des scientifiques qui y travaillent, c’est-à-dire le soir ou le week-end. « À partir du cycle des Love Stories, j’ai énormément travaillé parce qu’il y avait toujours une grève ou quelque chose. J’étais seule, c’étaient des moments heureux », se souvient-elle dans un entretien récent (Vera Molnar in conversation with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, 2018).

Love Story est une représentation poétique d’une communication parfois fluide, parfois difficile, entre deux entités : les deux carrés se chevauchent, ils subissent des déformations, connaissent des divergences, se rencontrent de nouveau, se séparent, se rapprochent. Ils s’invectivent et ils s’aiment, ils sont en désaccord ou en harmonie, ils s’orientent mutuellement sur la page. Peut-être constituent-ils également une représentation de deux dés jetés en l’air.

As a pioneer in the use of computers in artistic creation, Vera Molnar turned to geometric abstraction, working on form, its transformation and its movement as early as the 1950s. As a true visual artist, she explores lines, squares, white, black, grey, blue and red and brings out the unexpected and imaginary freedom through a series of transformations of forms worthy of scientific experimentation.

“The pictorial work is above all sensitive, it is addressed to the eye. It is for the human eye that I want to make images. The art of painting begins on the retina, first that of the painter, then that of the spectator? Art must be human, that is to say, it must conform to human nature.”

Véra Molnar is of Hungarian origin, but has lived in Paris since 1947. She therefore presents herself as a French and abstract painter, of the tendency that belongs to constructive art, in its most consequent and radical sense: that of systematic art, in which she has been engaged since 1950.

She participated in all the debates that led to the birth of kinetic art and enabled the creation of La Nouvelle Tendance and, from 1968 onwards, became one of the pioneers of the use of computers in artistic creation.

The representation of nature has never interested her, and when she tries to explain the real reasons for her choice to work on these forms alone, it is, she says, that “the simplicity of these forms still moves her”. Her art, conducted in an experimental way, is about the form, its transformation, its displacement, its perception. Her work is accompanied by an intense theoretical reflection on the means of creation and the mechanisms of vision. It has its origins in Mondrian, Malevich and the Zurich Concretes and finds numerous correspondences in all the work carried out in connection with the exact sciences and mathematics in particular.

The work, which for others could be systematic or even “machinic”, in reality aims to bring out the unexpected, freedom, the imaginary. The lines, for example, become “extravagant”, as the titles of some paintings tell us.

Pionnière de l’utilisation de l’ordinateur dans la création artistique, Vera Molnar se tourne vers l’abstraction géométrique, en travaillant sur la forme, sur sa transformation et sur son déplacement dès les années cinquante. En véritable plasticienne, elle explore la ligne, le carré, le blanc, le noir, les gris, les bleus, les rouges et fait surgir l’imprévu et la liberté imaginaire grâce à une série de transformations de formes dignes de l’expérimentation scientifique.

« L’œuvre picturale est avant tout sensible, elle s’adresse à l’œil. C’est pour l’œil humain que je veux faire des images. L’art de la peinture commence sur la rétine, d’abord celle du peintre, ensuite celle du spectateur…. L’art doit être humain, c’est-à-dire conforme à la nature humaine ». Véra Molnar

Véra Molnar est d’origine hongroise, elle vit à Paris depuis 1947.

Elle se présente donc comme française et peintre abstraite, de la tendance qui appartient à l’art constructif, dans son acception la plus conséquente, la plus radicale qui soit : celle de l’art systématique dans lequel elle est engagée depuis 1950.

Elle a participé à tous les débats qui ont animé la naissance de l’art cinétique et permis la création de La Nouvelle Tendance et est devenue à partir de 1968 l’une des pionnières de l’utilisation de l’ordinateur dans la création artistique.

La représentation de la nature ne l’a jamais intéressée, et, quand elle cherche à expliquer les véritables raisons de son choix de travailler sur ces seules formes, c’est, dit-elle, que « la simplicité de ces formes l’émeut encore et toujours ». Son art, conduit de façon expérimentale, porte sur la forme, sa transformation, son déplacement, sa perception. Son travail s’accompagne d’une intense réflexion théorique sur les moyens de la création et les mécanismes de la vision. Il a son origine chez Mondrian, Malevitch et les Concrets zurichois et trouve de nombreuses correspondances dans tous les travaux conduits en rapport avec les sciences exactes et les mathématiques en particulier.

Le travail, qui, chez d’autres, pourrait être systématique voire “machinique”, a en réalité pour but de faire surgir l’imprévu, la liberté, l’imaginaire. Les lignes, par exemple, deviennent « extravagantes », comme nous le précisent d’ailleurs les titres de certains tableaux.

Rebekka Seubert (1985) started her career after graduating from binational studies in cultural sciences (French-German Studies) at the Universities of Regensburg and Clermont-Ferrand, followed by her studies in Fine Art at École de Recherche Graphique, Brussels and at Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg. Her first experiences as curatorial assistant at the exhibition hall Portikus, Frankfurt, were followed by a Volontariat at Bonner Kunstverein. From the end of 2018 she worked with Annette Hans as artistic director of Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, Hamburg on solo-exhibitions by Dara Friedman and Annika Larsson. Through experimental formats such as Hi Ventilation and Realismus mit Schleife she brought young and more established artists in group exhibitions together and invited artists like assume vivid astro focus, Chris Reinecke or Juliette Blightman to Hamburg.

As a freelance curator Rebekka Seubert presented solo shows by Lucy Raven and Georges Adéagbo at Warburg Haus, Hamburg (co-curated with Prof. Petra Lange-Berndt) and together with artist Fion Pellacini she founded the temporary project space Il Caminetto in Hamburg.

Between 2014 ans 2016 she had a teaching assignment at Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg, upon invitation by Prof. Silke Grossmann.

Rebekka Seubert (1985) a commencé sa carrière après des études en sciences culturelles (études franco-allemandes) dans les universités de Ratisbonne et de Clermont-Ferrand, suivies d’études en beaux-arts à l’École de recherche graphique de Bruxelles et à la Hochschule für Bildende Künste de Hambourg.

Ses premières expériences en tant qu’assistante curatoriale à Portikus, Francfort, ont été suivies d’un Volontariat au Bonner Kunstverein. Depuis fin 2018, elle a travaillé avec Annette Hans en tant que directrice artistique du Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, Hambourg, sur des expositions individuelles de Dara Friedman et Annika Larsson. Grâce à des formats expérimentaux tels que Hi Ventilation et Realismus mit Schleife, elle a réuni de jeunes artistes et des artistes plus établis dans des expositions de groupe et a invité des artistes comme assume vivid astro focus, Chris Reinecke ou Juliette Blightman à Hambourg.

En tant que commissaire indépendante, Rebekka Seubert a présenté des expositions individuelles de Lucy Raven et Georges Adéagbo à la Warburg Haus, Hambourg (en collaboration avec le professeur Petra Lange-Berndt) et a fondé avec l’artiste Fion Pellacini l’espace de projet temporaire Il Caminetto à Hambourg.

Entre 2014 et 2016, elle a enseigné à la Hochschule für Bildende Künste, à Hambourg, à l’invitation de la professeur Silke Grossmann.

Mauricio Limón de León’s projects often entail research and collaboration with groups of individuals over extended periods of time. While his approach flirts with anthropology and psychology, it rejects both their constitutive distance and narrative trappings. In his work, association shuttles across registers in an infectious, promiscuous play of projections and transferals. Intimacy, vulnerability, and kinship—which, Ruha Benjamin reminds us, is always produced and imaginary1—critically merge to carve out spaces of hospitality, with all its productive tensions. Limon’s works also foreground embodied knowledges and communal practices that resist the logics of authorship or mastery, capital or extraction. In all this, his work is deeply—if not always evidently—political.