The Rhythm of Return

All inquiries have a moment in time. This moment is moved by the changing winds in Enrique Ramirez’ life, that are being redirected thanks to a new compass: his recently arrived daughter. Her presence has precipitated a new series of almost existential questions about his artistic practice. While the past has been a recurring motif in Ramirez’ work—his personal history, that of his home country, even the Global South—this moment marks a turn toward the future. It’s an invitation to consider the world that his generation will pass on to the next. Will his daughter be stranded by the climate crisis, or is there hope? In one of Ramirez’s text works, he points to “A flag searching for the wind so that we can move forward…” The flag here refers to those attached to the mast of the ship - that serve as an indicator of the wind’s direction. With the climate already a background and context in much of his work, perhaps his daughter is like that small flag, a point of attention, a flicker of suggestion moving the ship in a new direction. In other words: is the arrival of his daughter leading Ramirez to change course in search of the possible?

Like any personal revolution, with the onset of fatherhood, there is within it a sense of repetition, a rotating motion - a seemingly straight line forward that, if followed carefully, might just form a circle. As part of a generation born under a dictatorship, Ramirez’ line starts in Chile, a country that formed his understanding of the world and which cultivated his close bonds with the landscape. The land and motifs like “carrying the homeland with you” later became significant features of his work with image, film, sculpture and sound - but often in relationship with water, or at the edge of a lake or sea. The distance between his current location and Chile has always been measured in oceans.

For Ramirez, the home studio is his place of work, now in the periphery of his daughter’s wide-eyed observation, as he also keeps an eye on her. This routine of care, this generational cycle can’t help reminding him of his own childhood in Chile, and how he watched his father Hugo carefully dismantling sails, puzzling out how they are made, leaning over his sewing machine, assembling new patterns or repairing battles lost with the wind. The symbolism embedded in the act of reparation has an unexpected power, as one thinks about a generation in Chile recovering from a national trauma - rebuilding a future. This observable act of daily creation and transformation, Ramirez now understands, was very influential for his life: “It shaped my relationship with the world and the objects around me; at the same time, seeing how something can be taken apart, how something can be made anew, encouraged me to experiment.”

Although he currently lives in France and has spent a substantial portion of his life outside of Chile, he has always felt the need to trace the line back, navigating to the place that made him who he is. For a while this rhythmic motion of return shifted to seeking the land-beyond, toward new horizons - yet always with the word “foreigner” sewn inside his collar, regardless where his travels may have led. The temporal atmosphere of his early years in Europe, of being a visitor and then an immigrant, of a persistently unresolved sense of citizenship, and the feeling of one’s status in limbo has had a substantial imprint on his work. Perhaps the metaphor of adrift at sea with no land in sight, approaches the emotional uncertainty of such a state. Yet now, thanks to the family that conceived him and the family that’s presently in its early years of becoming, he has two anchors—in Santiago and in Paris.

As we walked along the Canal Saint-Martin in Paris on a cloudy day in mid September 2024, speaking mostly in English but switching into Spanish and French as needed to fill in the gaps, we talked about the future and the past. I asked about his first artwork that featured a sail, presented in Paris, but sourced from those collected (in the box pictured at the beginning of this text) by his father. The original sail was submitted for repair to Hugo’s taller (workshop), but upon inspection he found it to be paper-thin and thus unrepairable. After transporting the sail to France, the sail was installed upside down, to reference the shape of the South American continent, and tiled into equally sized frames that might, if stacked, fit into a suitcase. Inscribed on its surface is a subtle topography, each tile like a full-page spread of a book. Ramirez found the sun-worn material of this particular vela profoundly beautiful, a metaphor for the struggle of the voyage, and the courage needed to reach the destination. The gridded format is suggestive of attempts at orientation, like the longitude and latitude of a map. Hugo pointed out a zig-zag stitch adjacent to the ‘window’ of the sail, that was made by his original sewing machine, a Singer, back when Ramirez was a child. This mark leads back to the days when the taller was intertwined with their home in Santiago. “I saw him working with sails at home, all the time, and for me they were nothing special because they were always there. The sails were like everyday life, it was only later when I started studying film that I realized that working with sails was going to become a very important part of my life, and my work.” The inscription of a zigzag stitch, of Hugo’s history of work with the sail, and a marker in time of Enrique’s childhood becomes key:the sail as a living archive, one that is well worn and after a long life on the ocean, comes back to tell its story.

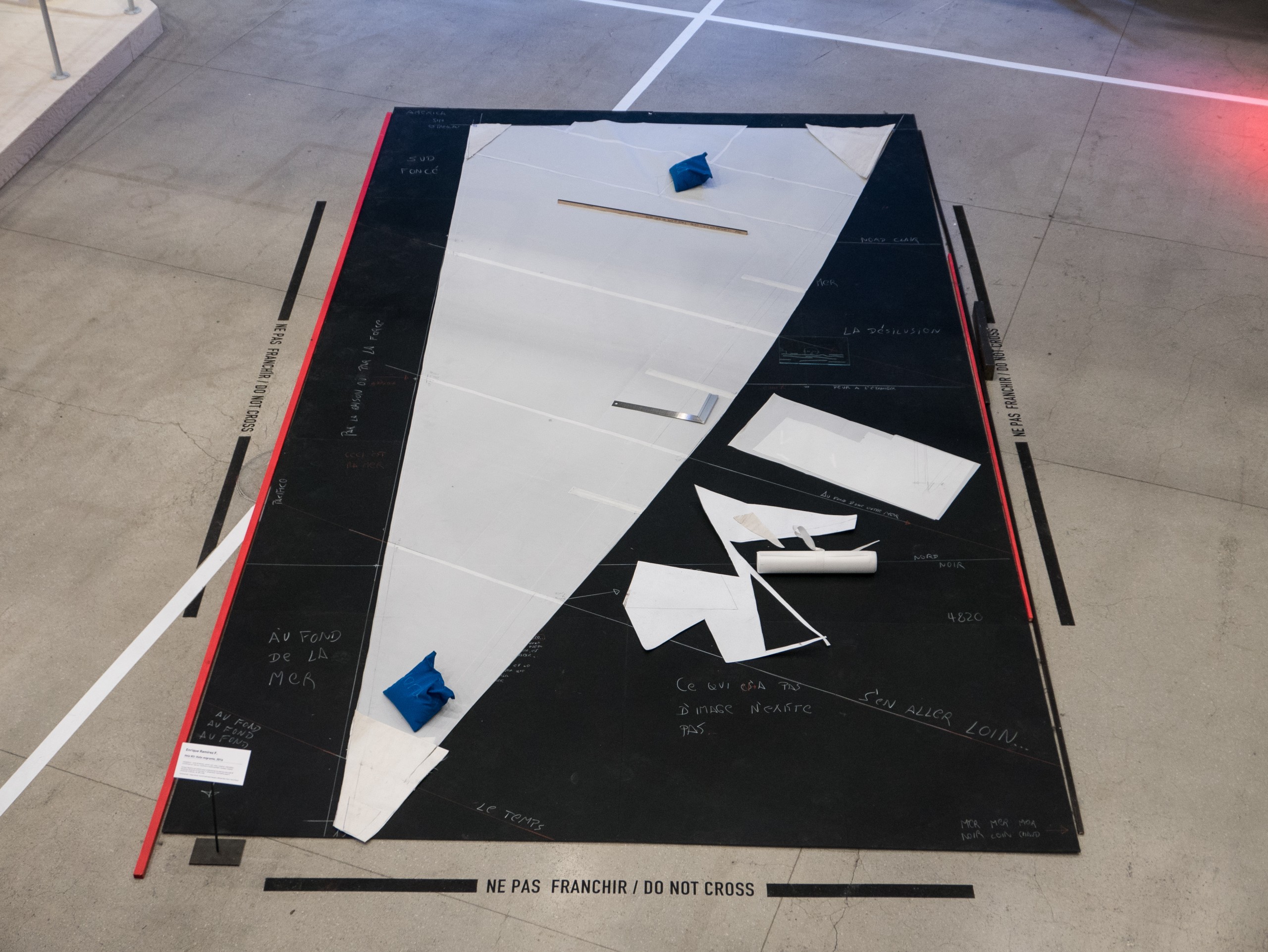

Over the years, Ramirez has also borrowed methods and practices from Hugo, a testament to a bond sustained despite the distance. In the images above: on the left, one finds the slate-black tile floor of Hugo’s taller in Santiago, upon which he makes marks and notes as he measures and pieces-together a sail - like a chalkboard that’s marked and wiped clean. In a phone conversation with Hugo, he notes “the whole floor acts as an extension of the sewing machine.” A representation of this floor appears in the form of black paper in a performance Ramirez staged at the Centre Pompidou, using red and white marks to inscribe outlines and poetic phrases in French and Spanish. Transforming Hugo’s original approach to marks and measurements, Ramirez noted directional markers and traced sections of the sail to establish a timeline. Among others, the phrase Norte Claro, Sur Oscuro, Aquacero Seguro appears here, first as a mnemonic device, a rhyme to read the skies, especially critical when sailing at sea where little is of greater importance than the weather. North Clear, South Dark, Downpour for sure, is also a double entendre referring to historically stormy relations between the Global North and the Global South, a motif that resurfaces in Ramirez’s work.

“A sail[boat] is an island on the sea, it’s a story left stranded…” To recognize a sailboat as subject to the forces of nature, moved only by the wind—as a collection of all of its voyages, all of the languages spoken aboard, the waves that crashed upon its deck, the people and things it has carried, and the storms it has survived—this is to understand the sailboat as an epic story. When I asked which of the many sails that Ramirez has made over the years was pivotal for his thinking, without hesitation he pointed to No. 5, The International Sail. The work was finished on-site, for an exhibition in San Francisco, and was the first time the surface of the sail included a hand-drawn cartographic layer. When I asked him about the name, he mentioned being moved by a headline in a San Francisco newspaper: We Are Not Immigrants, We Are International Workers. At the time Ramirez was approaching the end of a three-year period with a carte de sejour, or residence card in France, and he was feeling a distinct affinity with immigrants, amid news highlighting migrants arriving in crowded boats to various corners of Europe. The argument for an upgraded terminology to the status of international worker rather than immigrant, resonated with Ramirez. This shift in language is indicative of the fundamental need for dignity and respect in the context of a dominant, and for somehostile or confounding, host culture for anyone living abroad. No. 5also includes arupture piercing the glass of the frame: a small red flag, made with Hugo—en busca del viento perdido - that appears at the southernmost point of the transformed sail. The flag is planted at the center of a white five-pointed star surrounded by blue that references the flag of Chile—a pin in the map noting a point of origin. The stitches and marks added by Ramirez imply an alternative political geography in the South American continent, and clumps of cut-out stars and bright graphic lines are suggestive of new flags, and other formations of borders and countries—perhaps suggestive of the Bolivarian dream and historical aspiration of a united states of Latin America.

Creative forces are like the wind, they rise and fall, and like the purpose of the small red flag that Ramirez made with Hugo, they are always in search of the possible. But other forces are constant, like the son’s undeniable attachment to his father, a connection Ramirez no doubt seeks to nurture in his young daughter. Hugo keeps one of these small flags at his home in Chile, made of sections cut from the very first sail he produced in 1980, as a memory but also a reminder, a long thread of connection to his son, who has distributed other small sections of this sail, as part of projects around the world, including No. 5, The International Sail. The flag can be seen as a metaphor for orientation, Ramirez recounts, for being able to heed the precise direction of the wind, and thus for finding a way to navigate the present moment in a shifting context. In the end he confesses that, “working with sails is a form of recognition and love for my father.”

Beyond the symbolic reference to migration, the sail is also suggestive of the act of expedition, of travel, which is another constant in Ramirez’s practice. One that’s being challenged in the face of his new anchor. One might argue that it’s impossible to imagine his work without some form of travel—of walking (as in the widely exhibited film Un hombre que camina) and many other depictions in film and photography of the voyage. This restless and peripatetic spirit, of meandering and movement, was also inherited from his father, who traveled with their family across Chile. “He took us, every year, to a very special place, a small lake near a volcano in southern Chile. We always traveled by sailboat, and that relationship with travel was inherited 100 percent from my father. The only difference is that I went away and my father never left the territory of Chile.” From the multi-faceted project “Océan, 33°02’47”S / 51°04’00”N”, a more than 25 day-long film that captures his journey in a cargo ship from Valparaiso (Chile) to Dunkirk (France), to “Tidal Pulse”, an audio work whose protagonist is the noise of a navigating boat, travel not only shapes Ramirez’ practice but is the shape itself of the work, the pattern through which the piece comes into being.

Within the current changing winds of fatherhood, a point of recalibration or una travesía todavía incierta, his daughter now travels with him, continuing the circle of inherited movements. “I am living through something that I have never lived before” Ramirez explains, “I’m here on this new boat in front of the wind and the sail, trying to see where it will go, with many questions and with the beauty of seeing someone who wants to see what I would like to show her, which is only the good in the world. Everything bad loses meaning and everything good becomes stronger when you have a child, and I think I can take that into the realm of art.”

From a distance, a sailboat is a barely visible mark on the horizon, upon approach it is revealed: all the stitches in its sail speak of endless acts of return and reparation, of how a transfer of knowledge imprints and reimprints, how a practice is transformed through alterations, and how a history of experience on uncertain seas, with shifting winds can redirect the future.

Le rythme du retour

Toutes les interrogations intimes connaissent un moment décisif. Dans le cas d’Enrique Ramirez, ce moment a été déclenché par les vents fluctuants qui régissent son existence et le poussent dans une direction inédite grâce à la nouvelle boussole qui guide sa trajectoire : la naissance récente de sa fille. Sa présence a fait surgir une nouvelle série de questionnements quasi existentiels sur sa pratique artistique. Alors que le passé est un motif récurrent de son travail – ce qui n’est pas sans lien avec son histoire personnelle et la situation de son pays natal, voire même du Sud global – ce moment marque un tournant qui l’amène à regarder vers l’avenir et l’invite à s’interroger sur le monde que sa génération transmettra à la suivante. Sa fille sera-t-elle freinée dans son élan par la crise climatique ou peut-on encore avoir de l’espoir pour l’avenir ? Dans un de ses textes, Enrique Ramirez évoque « un drapeau à la recherche du vent qui nous permettra d’aller de l’avant… ». Le drapeau fait ici référence au morceau de tissu attaché au mât du navire qui sert d’indicateur de la direction du vent. La question climatique constituant déjà l’arrière-plan général qui définit une grande partie de son œuvre, sa fille est peut-être aujourd’hui comme ce petit drapeau sur la mer – un point d’attention, une lueur vacillante qui fait avancer le bateau dans une nouvelle direction. Pour le formuler autrement : la naissance de sa fille conduit-elle Enrique Ramirez à changer de cap à la recherche d’un futur possible ?

Comme toute révolution personnelle, l’expérience nouvelle de la paternité s’accompagne d’un sentiment de répétition et se traduit par un mouvement rotatif : une ligne qui semble avancer vers l’avant mais qui, si on la suit scrupuleusement, pourrait bien finir par former un cercle. Enrique Ramirez est issu d’une génération née sous une dictature. Sa trajectoire prend sa source au Chili, le pays à partir duquel s’est construite sa compréhension du monde et qui lui a permis de développer des liens étroits avec le paysage. Ce territoire et les thématiques qui en découlent, comme le fait de « porter sa terre natale avec soi », sont devenus des éléments importants de sa pratique artistique, qui l’amène à travailler avec la photographie, la vidéo, les objets, les textes et la musique pour créer des œuvres le plus souvent en relation avec la thématique de l’eau, ou dont le cadre se situe au bord d’un lac ou de la mer. La distance entre son lieu de résidence actuel et le Chili s’est toujours mesurée à l’échelle des océans.

L’appartement-atelier d’Enrique Ramirez est son lieu de création – un lieu désormais situé dans le périmètre d’observation de sa fille qui contemple le monde avec un regard neuf tandis que lui-même garde un œil sur elle tout en travaillant. Cette attention qu’il accorde à sa fille au quotidien et le cycle générationnel dans laquelle elle s’inscrit ne peut que lui rappeler sa propre enfance au Chili et la façon dont il observait son père, Hugo, démonter soigneusement des voiles de bateau, en essayant de comprendre comment elles étaient faites. Son père penché sur sa machine à coudre, assemblant de nouveaux modèles ou réparant les dégâts provoqués par des batailles perdues avec le vent. Le symbolisme associé à l’acte qui consiste à réparer revêt une force inattendue lorsque l’on songe à cette génération du Chili qui tente de se remettre d’un traumatisme national en essayant de se construire un nouvel avenir. Cet acte manifeste de création et de transformation dans lequel son père était quotidiennement engagé a eu, comme l’artiste le réalise aujourd’hui, une grande influence sur son parcours : « Cela a façonné ma relation avec le monde et les objets qui m’entourent ; en même temps, le fait de voir comment quelque chose peut être démonté avant d’être reconstruit de nouveau m’a encouragé à expérimenter. »

Bien qu’il vive actuellement en France et qu’il ait passé une grande partie de son existence en dehors du Chili, Enrique a toujours ressenti le besoin de remonter le fil de son existence, de retourner vers l’endroit qui a fait de lui ce qu’il est. Pendant un certain temps, ce mouvement rythmé par de nombreux allers et retours s’est transformé en une recherche de terres lointaines, une quête de nouveaux horizons – mais toujours avec le mot « étranger » gravé en filigrane, quel que soit l’endroit où ses voyages le menaient. Le contexte dans lequel se sont déroulées ses premières années en Europe, le fait d’y séjourner de manière provisoire puis en tant qu’immigrant, le sentiment persistant d’être un citoyen incomplet et d’avoir un statut extrêmement flou ont laissé une empreinte essentielle sur son œuvre. Peut-être que la métaphore qui veut que quelqu’un soit à la dérive sur la mer, sans aucune terre en vue se rapproche de l’incertitude émotionnelle que confère un tel statut. Pourtant, aujourd’hui, grâce à sa famille d’origine et à sa nouvelle famille en devenir, il possède deux points d’ancrage – à Santiago et à Paris.

Alors que nous marchions le long du canal Saint-Martin à Paris par une journée nuageuse de la mi-septembre 2024, discutant principalement en anglais mais basculant parfois vers l’espagnol ou le français pour combler nos lacunes, nous avons parlé de l’avenir et du passé. Nous avons interrogé Enrique Ramirez sur sa première création mettant en scène une voile de bateau présentée à Paris, réalisée à partir d’une voile provenant de la collection rassemblée par son père dans la boîte en bois dont l’image est reproduite au début de ce texte. La voile originale avait été déposée au taller (atelier de fabrication) d’Hugo Ramirez pour y être réparée, mais après inspection, ce dernier avait constaté qu’elle était aussi fine que du papier et donc irréparable. Après avoir été transportée en France, la voile fut installée à l’envers pour évoquer la forme du continent sud-américain, puis découpée pour former une mosaïque répartie dans des cadres d’égale dimension qui, une fois empilés les uns sur les autres, peuvent tenir dans une valise. Une topographie subtile est inscrite sur sa surface, chaque rectangle de voile évoquant la page d’un livre. Pour l’artiste, le matériau usé par le soleil de cette vela (« voile ») possède une beauté particulière car il constitue une métaphore des difficultés inhérentes au voyage et du courage nécessaire pour parvenir à destination.

Le format sous forme de grille représente une tentative de fixer des points de repère, telles les indications géographiques qui aident à déterminer la longitude et la latitude d’une carte. Hugo a ajouté une flèche indiquant un point zigzag situé près de la « fenêtre » de la voile, réalisé sur sa première machine à coudre Singer lorsque son fils était encore enfant. Cette inscription remonte à l’époque où son atelier était étroitement imbriqué avec leur lieu de vie à Santiago. « À la maison, je voyais mon père travailler en permanence sur des voiles de bateau et pour moi, elles n’avaient rien de spécial parce qu’elles faisaient partie de mon quotidien. Ce n’est que plus tard, lorsque j’ai commencé à étudier le cinéma, que j’ai réalisé que ce travail sur les voiles allait jouer un rôle essentiel dans ma vie et dans ma pratique artistique. » La flèche attirant l’attention sur le point zigzag, référence au travail effectué par son père sur la voile en même temps que marqueur temporel de l’enfance d’Enrique, prend ici tout son sens : la voile est une archive vivante portant la marque de l’usure du temps et qui, après de longues années passées à parcourir l’océan, revient raconter son histoire.

Au fil des ans, Enrique Ramirez a également emprunté des méthodes et des procédés à son père, témoignant ainsi du lien durable qui les unit malgré la distance. Une des photographies reproduites ci-dessus montre le sol recouvert de carrelage en ardoise de l’atelier d’Hugo à Santiago, qui lui sert à tracer des repères et à prendre des notes tandis qu’il mesure et assemble ses voiles, comme sur un tableau noir effaçable. Comme il l’a souligné lors de notre conversation téléphonique : « Le sol tout entier constitue une extension de la machine à coudre. » Une représentation de ce sol en ardoise sous forme de feuilles de papier noir apparaît dans l’installation imaginée par Enrique Ramirez pour le Centre Pompidou. À cette occasion, il s’est servi de marqueurs rouges et blancs pout tracer des points de repère et écrire des phrases poétiques en français et en espagnol. Transformant la méthode initiale de son père fondée sur une série de notes et de mesures, Enrique Ramirez a tracé des indications géographiques et a divisé la voile en différentes sections pour établir une succession de propositions. La phrase Norte Claro, Sur Oscuro, Aquacero Seguro, parmi d’autres formules, apparaît d’abord comme un moyen mnémotechnique, une rime pour lire le ciel (ce qui est particulièrement important lorsqu’on navigue en mer où les conditions météorologiques jouent un rôle essentiel). Cette phrase que l’on peut traduire par « Nord clair, Sud sombre, Déluge assuré » contient également un double sens qui fait référence aux relations historiquement houleuses entre le Nord et le Sud, un motif qui réapparaît souvent dans l’œuvre d’Enrique Ramirez.

« Un voilier est une île sur la mer, c’est une histoire abandonnée à son sort… » Reconnaître qu’un bateau à voile est soumis aux forces de la nature et ne se déplace que grâce au vent – qu’il constitue un florilège de tous les voyages qu’il a effectués, de toutes les langues parlées à bord, des vagues qui se sont écrasées sur son pont, des personnes et des objets qu’il a transportés, et des tempêtes auxquelles il a survécu –, c’est l’appréhender comme une histoire épique. Lorsque nous avons demandé à Enrique Ramirez laquelle des nombreuses « voiles » qu’il a créées au fil des ans s’est révélée jouer le rôle le plus essentiel dans son questionnement, il a désigné sans hésiter la cinquième de la série. Cette œuvre intitulée No. 5, The International Sail a été réalisée in situ, à l’occasion d’une exposition à San Francisco. C’était la première fois que la surface de la voile comportait des indications cartographiques dessinées à la main. Lorsque nous lui avons demandé pourquoi il avait choisi de l’appeler ainsi, il nous a répondu qu’il avait été frappé par le gros titre d’un journal de San Francisco annonçant : « Nous ne sommes pas des immigrés, nous sommes des travailleurs internationaux ». À l’époque, sa carte de séjour temporaire de trois ans qui lui permettait de résider en France arrivait à échéance. Il ressentait une analogie entre sa situation et celle des migrants, dans un contexte où leur arrivée dans des bateaux surpeuplés pour rejoindre différents pays européens ne cessait de faire la une des journaux. Les arguments invoqués pour actualiser le vocabulaire employé vis-à-vis des migrants de manière à leur faire faire obtenir le statut de travailleurs internationaux ont trouvé un écho auprès de l’artiste. Ce changement de terminologie témoigne du besoin fondamental de dignité et de respect de ces travailleurs dans un contexte où les pays d’accueil cherchent à intégrer toute personne étrangère dans une culture dominante qui peut sembler, pour certains, hostile ou déroutante. L’installation No. 5, The International Sail comporte également une rupture qui transperce littéralement le verre du cadre : un petit drapeau rouge fabriqué avec la complicité de Hugo – En busca del viento perdido (« À la recherche du vent perdu ») – qui apparaît au point situé le plus au sud de la voile transformée en carte géographique. Le drapeau est planté au milieu d’une étoile blanche à cinq branches entourée de bleu, métaphore du drapeau du Chili, telle une épingle sur la carte indiquant un point d’origine. Les points de couture et les repères ajoutés par l’artiste évoquent la possibilité d’une géographie politique alternative sur le continent sud-américain, tandis que les amas d’étoiles découpées et les aplats de couleur vive évoquent de nouveaux drapeaux et d’autres configurations de frontières et de pays – un clin d’œil, peut-être, à l’utopie bolivarienne et à l’aspiration historique à des « États-Unis d’Amérique Latine ».

Les forces créatrices sont comme le vent : elles vont et viennent. Tels les petits drapeaux rouges qu’Enrique a fabriqués avec son père, elles sont toujours à la recherche du possible. D’autres éléments demeurent néanmoins constants, comme l’attachement indéniable du fils à son père, un lien que l’artiste cherche sans doute à reproduire avec son propre enfant. Hugo conserve dans sa maison du Chili un de ces petits drapeaux créés à partir de fragments de tissu découpés dans la toute première voile qu’il a fabriquée en 1980. Ce drapeau constitue pour lui un souvenir tout autant qu’une trace tangible du fil qui le relie son fils, qui a lui-même disséminé à travers le monde d’autres fragments de cette voile dans le cadre de divers projets, notamment l’installation No. 5, The International Sail. « Le drapeau, explique Enrique, peut être considéré comme une métaphore de notre faculté d’orientation, de la capacité que nous avons de tenir compte de la direction précise du vent et, dans un contexte mouvant, de nous frayer un chemin dans le moment présent. » Comme il l’avoue finalement : « Travailler avec des voiles de bateau est une forme de reconnaissance envers mon père et une preuve d’amour envers lui ».

Au-delà de la référence symbolique à la migration, la voile évoque également le fait de partir en expédition et de voyager, autre constante de l’œuvre d’Enrique Ramirez. Cette habitude est aujourd’hui remise en question par son nouveau point d’ancrage lié à sa récente paternité. Il est presque impossible d’imaginer son travail sans une certaine forme de voyage – de cheminement, comme dans le film Un hombre que camina (« Un homme qui marche »), diffusé dans de nombreux lieux d’exposition, et comme dans d’autres de ses vidéos ou photographies axées sur la représentation du voyage. Cet esprit nomade et toujours en mouvement, de même que ce goût pour l’errance et le vagabondage, sont également un héritage de son père, qui voyageait avec sa famille à travers le Chili. « Il nous emmenait chaque année dans un endroit très particulier, un petit lac situé à proximité d’un volcan, au sud du Chili. Nous voyagions toujours à bord d’un voilier. Ma propre relation au voyage a été héritée à 100 % de mon père. La seule différence, c’est que je suis parti et que lui n’a jamais quitté le Chili. » Du projet multiforme Océan, 33°02’47”S / 51°04’00”N”, un film retraçant le voyage de vingt-cinq jours à bord d’un cargo qui l’a mené de Valparaiso à Dunkerque, à Tidal Pulse, une œuvre audio centrée sur l’enregistrement du bruit que fait un bateau en train de naviguer, le voyage ne façonne pas seulement la pratique artistique d’Enrique Ramirez : il est la forme même de l’œuvre, le modèle à travers lequel ses créations voient le jour.

Maintenant qu’il se retrouve aux prises avec les vents changeants de la paternité – une période de réajustement vécue comme una travesía todavía incierta (« une traversée encore incertaine ») –, sa fille voyage désormais avec lui, perpétuant le cycle de déplacements hérité de son propre père. « Je suis confronté à quelque chose que je n’avais jamais vécu auparavant, explique Enrique. Je me retrouve embarqué sur ce nouveau bateau, face au vent et à la voile, essayant de voir où cela va me mener. Cette situation s’accompagne de nombreuses interrogations, mais il s’agit également d’une expérience magnifique qui consiste à regarder un être vivant qui a véritablement envie de voir ce que je veux lui montrer, c’est-à-dire uniquement ce qu’il y a de bon dans le monde. Tout ce qui est mauvais perd de son sens et tout ce qui est bon devient plus fort lorsque vous avez un enfant. Je pense que je peux transposer cette expérience dans le domaine de l’art. »

Vu de loin, un voilier est une forme à peine visible sur l’horizon. Lorsqu’on s’en approche, il se révèle : toutes les coutures de sa voile évoquent des épisodes innombrables de réparation et de retour au point de départ. Elles racontent comment un transfert de connaissances est susceptible de laisser une empreinte durable qui se renouvelle sans cesse, comment une pratique se transforme à travers les modifications qui surviennent et, enfin, comment une histoire vécue sur des mers incertaines, avec des vents qui fluctuent, peut réorienter l’avenir.

Enrique Ramírez was born in 1979 in Santiago de Chile.

Since 2010, he lives and works between Paris (France) and Santiago (Chile).

He studied popular music and cinema in Chile before joining the postgraduate master in contemporary

art and new media at Le Fresnoy - Studio National des Arts Contemporains (Tourcoing, France). In 2013 he won the discovery price of Les Amis du Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France. He was nominated for the Prix Marcel Duchamp (France) in 2020, as well as the SAM art prize and the Meurice art prize (France) in 2014. He has since exhibited in some major places such as Palais de Tokyo, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris (France), Museo Amparo, Puebla (México), Museo de la memoria, Santiago (Chile), Parque de la Memoria and Centro Cultural MATTA, Buenos Aires (Argentina), Galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal (Canada), CCA – Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv (Israel), Kunsthalle Bielefeld (Germany). In 2017 he was part of the 57th Venice Biennale in the international exhibition “Viva Arte Viva” (curator Christine Macel). In 2022 Enrique has a major solo show at Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains (France) in dialogue with works from the Pinault collection (curators Caroline Bourgeois, Pascale Pronnier & Enrique Ramírez).

A major solo exhibition is planned for 2025 at the MNBA-Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago

(curator Sergio Edelsztein). His work is part of prestigious collections such as Centre Pompidou (Paris, France) ; Pinault Collection (Paris, France) ; MoMA (New York, USA) ; Kadist Art Foundation (San Francisco, USA) ; Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration (Paris, France) ; MAC-VAL (Vitry-sur-Seine, France) ; Pérez Art Museum (Miami, USA) ; Museo Ampáro (Puebla, Mexico) ; Fundacion AMA (Santiago, Chile) ;

Fundación Engel (Santiago, Chile), Collection Itaú cultural (São Paulo, Brazil), Museo de la Memoria y

los Derechos Humanos (Santiago, Chile) ; Fonds d’art contemporain - Paris Collections (Paris,

France), Frac Sud - Cité de l’art contemporain (Marseille, France), etc…

Enrique Ramírez’s work combines video, music, photography, installations and poetic narratives. Ramírez appreciates stories within stories, fictions straddling countries and epochs, the mirages between dream and reality. This Chilean artist often uses image and sound to construct a profusion of intrigues and to occupy the equilibrium between the poetic and the political. His imaginary worlds are attached to one obsessional element: his thinking starts with the sea, a space for memory in perpetual movement, a space for narrative projections where the fate of Chile intersects with grand narratives of voyage, conquest and migratory flows. His images speak of the sparkle of a truth in permanent flight, the backwash of history, always repeating and never the same.

Enrique Ramírez est né en 1979 à Santiago du Chili.

Depuis 2010, il vit et travaille entre Paris (France) et Santiago (Chili).

Il a étudié la musique populaire et le cinéma au Chili avant de rejoindre en 2007 Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains (Tourcoing, France). En 2013, il a remporté́ le Prix Découverte des Amis du Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France. Il a été nommé pour le Prix Marcel Duchamp (France) en 2020, ainsi que pour le prix SAM pour l’art contemporain et le Prix Meurice pour l’art contemporain (France) en 2014. Il a notamment exposé au Palais de Tokyo et au Centre Pompidou à Paris (France), au Museo Amparo, Puebla (Mexique), au Musée de la Mémoire, Santiago (Chili), au Parque de la Memoria et au Centre Culturel MATTA, Buenos Aires (Argentine), à la galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal (Canada), au CCA – Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv (Israël), à la Kunsthalle Bielefeld (Allemagne)… En 2017, il fait partie de la 57e Biennale de Venise dans l’exposition internationale « Viva Arte Viva » (commissaire Christine Macel). En 2022, Enrique a bénéficié d’une grande exposition personnelle au Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains (France) en dialogue avec des œuvres de la collection Pinault (commissaires Caroline Bourgeois, Pascale Pronnier & Enrique Ramírez).

Une grande exposition personnelle est en préparation pour 2025 au MNBA-Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago (commissaire Sergio Edelsztein). Son travail fait partie de collections prestigieuses telles que le Centre Pompidou (Paris, France) ; Collection Pinault (Paris, France) ; MoMA (New York, États-Unis) ; Kadist Art Foundation (San Francisco, États-Unis) ; Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration (Paris, France) ; MAC-VAL (Vitrysur-Seine, France) ; Pérez Art Museum (Miami, États-Unis) ; Museo Ampáro (Puebla, Mexique) ; Fundacion AMA (Santiago, Chili) ; Fundación Engel (Santiago, Chili) ; Collection Itaú cultural (São Paulo, Brésil) ; Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Santiago, Chili) ; Fonds d’art contemporain - Paris Collections (Paris, France), Frac Sud - Cité de l’art contemporain (Marseille, France), etc…

Son travail combine la vidéo, la photographie, le son, les installations et les récits poétiques. Enrique Ramírez aime les histoires à tiroirs, les fictions chevauchant les pays et les époques, les mirages entre songe et réalité́. L’œuvre de cet artiste chilien, qui vit et travaille entre le Chili et la France, se concentre sur la forme vidéographique et les installations : c’est souvent par l’image et le son qu’il construit ses intrigues foisonnantes et s’insinue en équilibre entre le poétique et le politique. Son imaginaire gigogne s’arrime dans un élément obsessionnel — il pense à partir de la mer, espace mémoriel en perpétuel mouvement, espace de projections narratives où s’entrecroisent le destin du Chili et les grands récits liés aux voyages, aux conquêtes, aux flux migratoires. Liquides, ses images disent le miroitement d’une vérité́ toujours fuyante, le ressac de l’Histoire, toujours la même, jamais pareille.

Joseph del Pesco is a peripatetic writer, curator and perennial collaborator. For more than a decade he’s been Director, and starting in 2016 became International Director of KADIST—a network-driven contemporary arts organization with headquarters in Paris. He’s known for creating the first international residency for art magazines, reimagining an historic artist contract to support a charity chosen by the artist, and establishing a free-school aggregating events across the city. Working with Kadist and independently, he’s organized numerous exhibitions, screenings and projects at institutions such as Centre Pompidou, MACO Oaxaca, MACBA, moCa Cleveland, The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Center for Contemporary Art Tel Aviv, CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). He’s also been a guest of various residency programs including Fogo Island Arts, SOMA, Beta-Local, The Luminary, ArtPort, and Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo. His writing has been published in dozens of catalogs, magazines, and books. His sold-out collection of short stories about imaginary museums, “The Museum Took a Few Minutes To Collect Itself,” was published by Art Metropole (Toronto) in 2018. His website: www.pleaseteleport.me

Enar de Dios Rodríguez is a visual artist interested in demonstrating how economic, sociopolitical, historical, and environmental aspects intersect with each other. Through the use of a diverse range of media, including video, photography, and installation, her recent projects have focused on acts of territorialization, examining their origins, repercussions, and the requisite technologies of control essential for their execution. Enar’s artistic practice is research-based, rooted in interdisciplinary investigations, wherein the selective process of existing visual and textual material serves as a starting point for an exploration of the poetic and its political applicability. Understanding art as an affective form of knowledge-production, and inspired by feminist, posthumanist, and decolonial perspectives, her projects ultimately aim to creatively sabotage the imposed future. Her website: https://enardediosrodriguez.com

Joseph del Pesco est un écrivain nomade, un commissaire exposition et un éternel initiateur de projets artistiques. Depuis plus de dix ans, il est directeur (directeur international depuis 2016) de KADIST, une organisation d’art contemporain s’appuyant sur un large réseau de conseillers dont le siège se trouve à Paris. On lui doit un certain nombre de réalisations notables, comme la création de la première résidence internationale dédiée aux revues d’art ; la création, à partir d’un contrat type, d’un nouveau contrat de production d’œuvre d’art permettant de soutenir une association caritative choisie par l’artiste ; et l’ouverture d’une école gratuite s’articulant autour de divers événements programmés dans plusieurs lieux différents. En collaboration avec KADIST ou en solo, il a organisé de nombreuses expositions, projections et projets dans des institutions telles que le Centre Pompidou, le MACO Oaxaca, le MACBA, le moCa Cleveland, le Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, le San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, le Center for Contemporary Art Tel Aviv, le CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts et la Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). Il a également été invité à participer à divers programmes de résidence organisés par les centres artistiques suivants : le Fogo Island Arts, le SOMA, le Beta-Local, The Luminary, l’ArtPort et la Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo. Ses textes ont été publiés dans de multiples catalogues, magazines et livres. Son recueil (aujourd’hui épuisé) de nouvelles sur des musées imaginaires, The Museum Took a Few Minutes To Collect Itself, a été publié par Art Metropole (Toronto) en 2018. www.pleaseteleport.me

Enar de Dios Rodríguez est une artiste qui cherche, à travers ses créations, à mettre en évidence la manière dont les enjeux économiques, sociopolitiques, historiques et environnementaux se recoupent les uns les autres. Ses projets récents, qui s’articulent autour d’une grande variété de supports comme la vidéo, la photographie et l’installation, portent sur les processus de territorialisation, dont elle imagine les origines, les répercussions et les technologies de contrôle nécessaires à leur mise en œuvre. Enar fonde sa pratique artistique sur des travaux de recherche, et notamment des enquêtes interdisciplinaires, où le processus de sélection d’un matériel visuel et textuel existant sert de point de départ à une exploration de la forme poétique et de ses possibles déclinaisons politiques. En envisageant l’art comme une forme de production de connaissances ayant un fort contenu émotionnel et en se nourrissant des théories féministes, posthumanistes et décoloniales, ses projets visent en définitive à saboter de manière créative l’avenir que l’on cherche à nous imposer. https://enardediosrodriguez.com

Dans ses œuvres, Mimosa Echard fait fi des classifications traditionnelles et concilie des facettes opposées. Artiste plutôt intuitive, elle a un sens aigu des matériaux et les combine de manière passionnante. Au-delà de leur vigoureuse présence matérielle, ses œuvres sont animées d’une puissante énergie souterraine. De la sublimation en quelque sorte. L’idée de contagion est également présente. Dans ses œuvres Je ressens souvent un équilibre précaire entre le séduisant, voire l’érotique, et le laid, le repoussant et le lugubre. (…) Mimosa Echard propose des associations sans logique, mélange et combine jusqu’à obtenir une contradiction, une ambivalence ou un paradoxe. On retrouve un lien avec l’intérieur et l’extérieur du corps humain et les fluides corporels. La pellicule rose, Le camping, le sol dur, la nausée tous les matins, les règles (2020), spécialement réalisée pour Fluid Desires participe de cette idée, mais annonce aussi une nouvelle direction.