Stumbling upon the work of Nicolas Chardon without seeking to put it in a box or find references to it in the history of painting, experiencing a moment in which a certain magic operates: we contemplate, question ourselves, look more closely and very soon a smile plays on our lips, as we manage to discern what presents itself to us. There is no doubt that the person behind this work professes a true love of painting and demonstrates a subtle irony, the lightness of which is almost lilting and beyond the cliché of the artist expressing onto the canvas his innermost feelings. We simultaneously perceive the seriousness of the work in an almost intuitive way and a deep analysis of the conditions of painting, techniques and materials, their possibilities of bearing meaning but also their source of stimulation, without managing or wanting to express this directly with words.

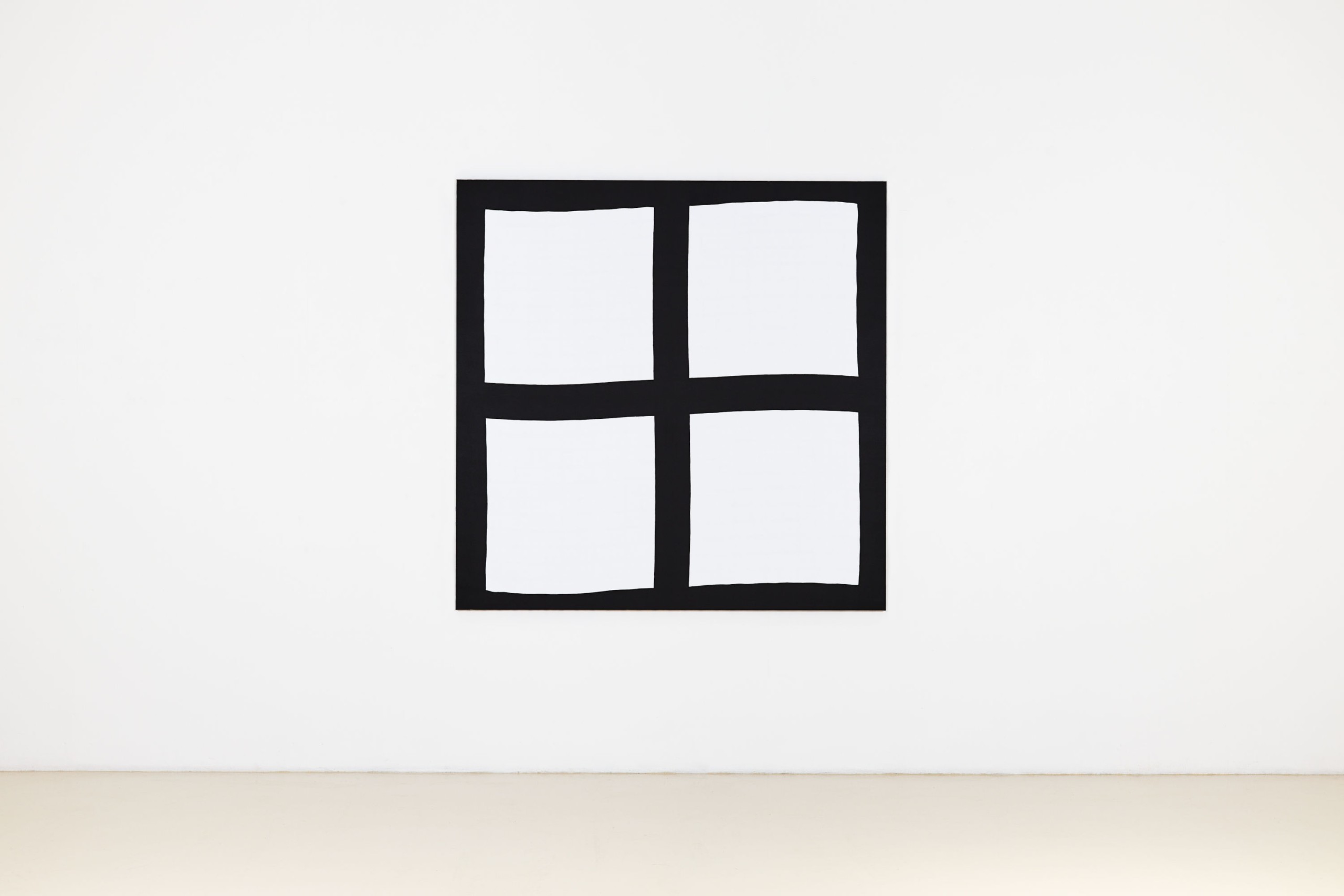

A first visit to an exhibition by Nicolas Chardon requires a few explanations: the right angle dominates and the basic square shape is almost omnipresent. And yet the opposite is just as valid: you will find no angle measuring exactly 90 degrees; with naturally twisted shapes, appearing almost in an ad hoc manner on the canvases. Here we are promptly mid-ontological thought, so to speak; we start thinking about visual codes and the principles of placement, conventions and cultural connections with respect to the interpretation of reality. Although distinguishing a bona fide geometric square comprising four equal sides and four right angles on Nicolas Chardon’s paintings is purely a matter of chance, we always describe the shapes as regular and recurrent orthogonal constructions that have been deformed and twisted in one way or another, and not freehand, almost elusive surfaces, from a mathematical point of view.

The fact that the models that dictate a certain vision of the world to us are essentially based on regularity, shared laws and conventions also means that an anarchic or at least humorous potential inhabits these seemingly deliberate transgressions. Apparently, there is someone who does not take this world that we have created that seriously, instead orienting us in daily life and helping us to avoid feeling overcome by possibilities, playing on rules and conventions, circumventing structures and expectations. It is important to understand that the artist, just like the viewers, finds a certain freedom in this: in the foreground, the theoretical discourse, which the neophytic audience can easily feel themselves excluded from, makes way for direct experience, the comparison of artistic creation with a clearly deviant vision of it.

Nicolas Chardon manages to create this productive irritation by shifting what we’re used to seeing. Even when he chooses the material of his medium, he propels painting into the world of everyday life: he replaces the traditional painting canvas by ordinary fabrics whose bold checkerboard motifs are the result of the expertise of various crafts, like Vichy, Scottish, or madras fabrics used to make everything from tea towels to clothes. Once mounted onto a frame, they already form a kind of predefined artwork consisting of lines, colours, and layout. This composition is nevertheless strongly disrupted by a highly regular woven pattern that is totally distended and deformed in an unrestrained way by the tension exerted during its attachment over the frame. The rigorous grid of the pattern transforms itself into an agitated ocean of forms that have lost all notion of limits, or in more mathematical terms, a simple intervention transforms an Euclidian space into dimension 1 varieties from the theory of relativity.

After applying a first transparent layer onto the taut fabrics, which always allows the pattern to emerge, Nicolas Chardon imposed his own order on this system that he invented and manipulated: he mostly uses black acrylic paint, but also red or other colours from time to time, to paint along predefined lineatures, bringing forms together and creating larger “squares” and “rectangles” (which really no longer strictly resemble these shapes), composing meanders, mazes and lettering, all deriving from the grid. Whereas the original pattern remains visible on the blocks and confers something tangible to the painting, the white colour, which surrounds it and traditionally represents the background, comes in at the end, like some sort of frame surrounding the elements. We still think it’s possible to describe them geometrically and yet we are immediately called to order – this would equate to radically simplifying their existence. We really start to rack our brains from the moment we become aware of the imprecise nature of our own interpretation, including that of the combinations of painted letters and some of the words they give rise to. Are these paintings abstract (which they sometimes proclaim to be), tangible or even figurative, are they ironic, discursive or intuitive, are they solitary, series or installations – do they represent a new order, the gateway to chaos or all of the above?

The opportune time has come for evoking the Black Square shown by Kazimir Malevich in 1915, representing both the first and final points in painting, so as to free the painting from a representative stranglehold and re-establish the capacity for thought in art, as the essential principle of human knowledge. We can also refer to Marcel Duchamp and the ready-made, thanks to which objects from everyday life were, for the first time, considered worthy of art. It is also important to insist on the fact that Nicolas Chardon already quoted at the start of his career – with remarkable consequences – the legendary exhibition 0.10 in Saint Petersburg with a subtle irony and disarming love of painting, from that moment on and up until the present day, he drags away the incunable of the “black square”, through all modulations imaginable, from the abandonment in the streets of Rome to the structures built with refinement. Some focus on these references taken from art history right from their first encounter with the artist’s works, but their gaze later becomes somewhat diverted. Ultimately, we are always brought back to our own perception, to the joy of discovering and deciphering, to the physical experience of the untouchable. What could be more beautiful for an exhibition? As Nicolas Chardon so aptly puts it: “By demystifying the origin … and the end… , the artwork gains access to a true material presence, I’d even say a concrete one.”

Tomber par hasard sur l’œuvre de Nicolas Chardon sans chercher à la mettre dans une case ni à lui trouver de références dans l’histoire de la peinture, et vivre un instant où opère une certaine magie : nous contemplons, nous nous interrogeons, nous regardons de plus près et très rapidement se dessine un sourire sur notre visage, car nous arrivons à cerner ce qui se présente à nous. Il ne fait aucun doute que la personne derrière cette œuvre voue un véritable amour au tableau et fait preuve d’une ironie subtile, dont la légèreté est pour ainsi dire dansante et au-delà du cliché de l’artiste exprimant sur sa toile ce qu’il ressent en son for intérieur. Nous percevons à la fois le sérieux du travail de manière quasi intuitive et une réflexion profonde sur les conditions de la peinture, la technique et les matériaux, leurs possibilités à être porteuses de sens mais aussi leur source de stimulation, sans pouvoir ou vouloir l’exprimer directement avec des mots.

La première visite d’une exposition de Nicolas Chardon nécessite quelques explications : l’angle droit domine et la forme de base du carré est quasi omniprésente. Et pourtant, le contraire est tout aussi valable : en effet, vous ne trouverez aucun angle mesurant exactement 90 degrés ; des formes naturellement tordues et apparaissent de manière quasi inconstante sur les toiles. Nous voilà promptement en pleine réflexion pour ainsi dire ontologique sur les codes visuels et les principes d’ordre, les conventions et les accords culturels vis-à-vis de l’interprétation de la réalité. Bien que le fait de distinguer un véritable carré géométrique composé de quatre côtés égaux et de quatre angles droits sur les tableaux de Nicolas Chardon relève du pur hasard, nous décrirons toujours les formes comme des constructions orthogonales régulières et récurrentes, qui ont été déformées et tordues d’une manière ou d’une autre, et non des surfaces libres quasi insaisissables d’un point de vue mathématique.

Le fait que les modèles qui nous dictent une certaine vision du monde se basent essentiellement sur la régularité, les lois et les conventions communes a également pour conséquence qu’un potentiel anarchique, ou du moins humoristique, habite ces transgressions à l’évidence volontaires. Il existe visiblement une personne qui ne prend pas tellement au sérieux ce monde que nous avons créé pour nous orienter au quotidien et ne pas nous sentir dépassés par les possibilités, qui joue avec les règles et les conventions, qui contourne les structures et les attentes. Il est important de comprendre que l’artiste tout comme les contemplateurs y trouvent une certaine liberté : au premier plan, le discours théorique, dont le public néophyte peut facilement se sentir exclu, laisse sa place à l’expérience directe, la comparaison de la création artistique avec une vision déviant clairement de celle-ci.

Nicolas Chardon réussit à créer cette irritation productive en bousculant ce que nous avons l’habitude de voir. Même lorsqu’il choisit le matériau de son support, il propulse la peinture dans le monde de la vie quotidienne : il remplace la toile à peindre traditionnelle par des tissus ordinaires dont les motifs en damier dominants sont le résultat du savoir-faire de divers artisanats, comme les tissus Vichy, écossais ou madras utilisés pour confectionner aussi bien des torchons de cuisine que des vêtements. Une fois montés sur un châssis, ils forment déjà une sorte de tableau prédéfini constitué de lignes, de couleurs et d’un ordre. Cet ordre est toutefois fortement perturbé par un motif de tissage à la grande régularité qui est totalement distendu et déformé de manière incontrôlée par la tension exercée lors de la fixation sur le châssis. La grille rigoureuse du motif se transforme en océan agité de formes ayant perdu toute notion de limite, ou en termes plus mathématiques : une simple intervention transforme un espace euclidien en variétés de dimension 1 du principe de la relativité.

Après avoir appliqué une première couche transparente sur le tissu sous tension, laquelle laisse toujours transparaître le motif, Nicolas Chardon impose son propre ordre à ce système trouvé et manipulé : il utilise la plupart du temps de l’acrylique noire, mais aussi du rouge ou d’autres couleurs de temps à autre, pour peindre le long des linéatures prédéfinies, rassembler les formes et créer des « carrés » et « rectangles » plus grands (qui, justement, n’en sont plus vraiment), composer des méandres, des labyrinthes et des lettres, découlant tous de la grille. Tandis que le motif d’origine reste visible au niveau des tranches et confère quelque chose de tangible au tableau, la couleur blanche, qui l’entoure et qui représente traditionnellement le fond, arrive en dernière position, comme une sorte de cadre entourant les éléments. Nous croyons toujours possible de les décrire de manière géométrique et pourtant nous sommes aussitôt rappelés à l’ordre – cela équivaudrait à simplifier radicalement leur existence. Nous commençons réellement à nous triturer les méninges à partir du moment où nous prenons conscience du flou de notre propre interprétation, y compris celui des combinaisons de lettres peintes et des mots en résultant. Ces tableaux sont-ils abstraits (ce qu’ils proclament être parfois), concrets ou même figuratifs, sont-ils ironiques, discursifs ou intuitifs, sont-ils des solitaires, des séries ou des installations – représentent-ils un nouvel ordre, la porte du chaos ou alors tout à la fois ?

Le moment opportun est arrivé pour évoquer le « Carré noir », exposé par Kasimir Malevitch en 1915, représentant à la fois le point initial et le point final dans la peinture, afin de libérer le tableau d’une étreinte représentative et de rétablir la capacité de pensée dans l’art en tant que principe de connaissance humaine essentielle. Nous pouvons également faire référence à Marcel Duchamp et au ready-made, grâce auquel des objets de la vie quotidienne ont été considérés pour la première fois dignes de l’art. Il faudrait également insister sur le fait que Nicolas Chardon citait, avec des conséquences remarquables, déjà au début de sa carrière la légendaire Exposition « 0,10 » de Saint-Pétersbourg avec une ironie subtile et un amour désarmant pour la peinture. Dès lors et jusqu’à aujourd’hui il entraîne l’incunable du « Carré noir » à travers toutes les modulations imaginables, de l’abandon dans les rues de Rome aux structures construites avec raffinement. Certains se focalisent sur ces références tirées de l’histoire de l’art dès leur première rencontre avec les œuvres de l’artiste, mais leur regard est ainsi quelque peu détourné. En fin de compte, nous sommes toujours renvoyés à notre propre perception, à la joie de découvrir et de décrypter, à l’expérience physique de l’intouchable. Que peut-il y avoir de plus beau dans une exposition ? Comme le dit si bien Nicolas Chardon : « En démystifiant l’origine (…) et la fin (…), l’œuvre accède à une véritable présence matérielle, je dirais même concrète. »

Nicolas Chardon graduated from ENSBA Paris in 1997.

He was a resident at the Villa Medici, French Academy in Rome in 2008 - 2009.

He is co-founder of the alternative school BABA and of the publishing house CONNOISSEURS.

He teaches painting at the HEAD in Geneva.

He is represented by Galerie Laurent Godin (Paris), Galerie van Gelder (Amsterdam) and Gallery Shilla (Daegu - Seoul).

Since the end of the 90’s his work is regularly shown in solo and group exhibitions in France and abroad. He is present in important private and public collections, such as the Centre Pompidou - Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, the MUDAM - Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean in Luxembourg, the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain in Strasbourg, the Musée d’Arts de Nantes, the Musée Voorlinden in Wassenaar (NL), the Meritz Foundation in Seoul, the Marta Collection in Herford and EPO in Munich.

He has participated in numerous exhibitions including La Force de l’Art at the Grand Palais in Paris, Peinture / Malerei at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin, Seconde main at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Tableaux at the Magasin in Grenoble, Dystotal at the Ludwig Forum in Aachen, Revolution in Red-Yellow-Blue at the Marta Herford, Museum for Art Architecture Design in Herford.

In 2012 the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Strasbourg offered him his first museum monograph. In 2018 he had his first institutional exhibition in Germany at the Kunsthalle in Bremerhaven.

In 2022 and 2023, in duo with Karina Bisch, he will carry out two major projects, at the MAC VAL in Vitry-sur-Seine and at the Kunstmuseum in Bochum.

www.nicolaschardon.net

Nicolas Chardon est diplômé de l’ENSBA Paris en 1997.

Il a été pensionnaire à la Villa Médicis, Académie de France à Rome en 2008 - 2009.

Il est co-fondateur de l’école alternative BABA et de la maison d’éditions CONNOISSEURS.

Il enseigne la peinture à la HEAD à Genève.

Il est représenté par la Galerie Laurent Godin (Paris), la Galerie van Gelder (Amsterdam) et la Gallery Shilla (Daegu – Seoul).

Depuis la fin des années 90 son travail est régulièrement montré dans des expositions individuelles et collectives en France et à l’étranger. Il est présent dans d’importantes collections privées et publiques, telles que Le Centre Pompidou - Musée National d’Art Moderne à Paris, le MUDAM - Musée d’Art moderne Grand-Duc Jean à Luxembourg, le Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, le Musée d’Arts de Nantes, le Musée Voorlinden à Wassenaar (NL), la Fondation Meritz à Séoul, la collection Marta à Herford et EPO à Munich.

Il a participé à de nombreuses expositions parmi lesquelles La Force de l’Art au Grand Palais à Paris, Peinture / Malerei au Martin Gropius Bau à Berlin, Seconde main au Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Tableaux au Magasin à Grenoble, Dystotal au Ludwig Forum à Aachen, Revolution in Red-Yellow-Blue au musée Marta à Herford.

En 2012 le Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg lui offrait sa première monographie muséale. En 2018 Il réalisait sa première exposition institutionnelle en Allemagne à la Kunsthalle de Bremerhaven.

En 2022 et 2023, en duo avec Karina Bisch, il réalise deux projets d’envergures, au MAC VAL à Vitry-sur-Seine et au Kunstmuseum de Bochum.

www.nicolaschardon.net

Roland Nachtigäller studied art, visual communication, German Language & literature, and media education in Kassel, Germany. After completing a research assistantship at Kunsthalle Museum Fridericianum in Kassel, he joined the management team of DOCUMENTA IX in 1991. He subsequently pursued numerous exhibition projects as a freelance author and curator, such as the kunstwegen sculpture project in 1998, Feldversuche in 2002 or raumsichten in 2012. Before being appointed Artistic Director of the Marta Herford Museum, Nachtigäller was Director of Städtische Galerie Nordhorn between 2003 and 2008. The accolades that Marta Herford has won under his directorship include being voted Museum of the Year 2014 by the AICA International Association of Art Critics. After 13 years of successfully developing this iconic museum (built by Frank Gehry), he moved to the Rhineland at the beginning of 2022 to assume responsibility for the Insel Hombroich Foundation and Museum. He is the author of numerous catalogue, book and blog articles on contemporary art.

Roland Nachtigäller a étudié l’art, la communication visuelle, la langue et la littérature allemandes, et l’éducation aux médias à Kassel, en Allemagne. Après avoir effectué un assistanat de recherche au Kunsthalle Museum Fridericianum de Kassel, il a rejoint l’équipe de direction de DOCUMENTA IX en 1991. Il a ensuite poursuivi de nombreux projets d’exposition en tant qu’auteur et commissaire d’exposition indépendant, comme le projet de sculpture kunstwegen en 1998, Feldversuche en 2002 ou raumsichten en 2012. Avant d’être nommée directeur artistique du Marta Herford Museum, Nachtigäller a été directeur de la Städtische Galerie Nordhorn entre 2003 et 2008. Parmi les distinctions que le Marta Herford a obtenues sous sa direction, il a notamment été élu musée de l’année 2014 par l’Association internationale des critiques d’art (AICA). Après avoir développé avec succès pendant 13 ans ce musée emblématique (construit par Frank Gehry), il a déménagé en Rhénanie au début de 2022 pour assumer la direction de la Fondation et du Musée Insel Hombroich. Il est l’auteur de nombreux articles de catalogues, de livres et de blogs sur l’art contemporain.

Marie Maillard s’appuie sur des formes et des motifs existants, elle doute de la perception et questionne la réalité, trouve le jeu entre présence et absence intrigant et recherche des moyens contemporains de produire et de diffuser l’art. Marie Maillard s’intéresse également à l’essence de la matière et aux matériaux du futur, elle anticipe des technologies futures qui permettraient des transformations de la matière en modifiant leur structure moléculaire. De cette façon, le marbre, le bois, la pierre ou le métal pourraient devenir transparents voire liquides et la branche pourrait se transformer en matière inorganique telle que le verre ou l’eau (‘TWIG 1808‘, 2018).